I started this newsletter just over a year ago, and in that time we’ve covered a lot of ground. My goal in writing has been to share one main idea:

Due to shifts in technology and society, the shape of our cities is poised to change dramatically over the next generation. One day we’ll recognize the suburban era has come to a close, and something else has replaced it. A post-suburban future, if you will. I think this future is inevitable, but it’s up to us to shape things for better or worse in our communities. Cities and towns that cling to the suburban pattern will struggle and fall behind, but cities that look forward and adapt will emerge healthier and happier.

Today’s post is a reflection and recap of everything I wrote in the past year. I’ll walk through this year’s key ideas, linking to the posts where I elaborated on them, and concluding with the key takeaways for cities.

Note (1): As a recap post I’m doing something different with the formatting — all the links are to the previous articles that I’m recapping. Links to other sources are in the footnotes.

Note (2): this post is based on my recent talk for the Strong Towns National Gathering, so if you were there for the talk, this will sound familiar.

(1) We struggle to understand change

Before we get into city-specific discussion, there’s an idea we need to anchor in our minds: it’s hard to understand big changes. This is partly because individuals only get to experience one lifetime, but mostly because change happens in S-Curves.

This pattern is near universal1. Nobody sees big changes coming, and then they’re old news, the world has always been this way.

When we talk about potential solutions to problems our cities and towns face, people are often dismissive. But consider how much change we’ve seen in one lifetime! My dad was born in Texas in 1955, at that point, outside the larger cities, electricity was new. The Texas Hill country wasn’t fully electrified until 1948, but it has transformed from a rural backwater to a thriving modern metropolis in a single lifetime.

We also often misremember the timeline. Americans tend to think of modern suburbia as appearing alongside the Interstate Highways in the 1950s and 60s. In reality, the suburban model first emerged in the 1860s, and was mostly established by the 1930’s. And while car-only transportation eventually became the defining characteristic of suburbia, the evolution of the suburbs depended less on widespread car adoption, and far, far less on the construction of the Interstate Highways, than we think. In many ways the construction of the Interstates (completed in 1992!) were the climax or culmination of the suburban era, more than its harbinger.

Finally, we tend to overestimate what we can do in a short time, but wildly underestimate what can do over a long time. The Sagrada Familia will soon be completed after nearly 150 years of construction2. The city of Amsterdam reinvented itself around bikes and pedestrians, but the transformation started nearly 50 years ago and is still unfolding3. As a younger adult I found it discouraging to think about projects that couldn’t be completed in time for me to personally benefit in the near future, but I think part of growing up is recognizing the immense power of a longer horizon.

So, as we consider the rest of the story, keep this idea in mind: it’s hard to understand change.

(2) To understand where our cities might go, we need to understand how we got here

To start we have to understand what cities actually are. In the wonkiest possible terms — cities are complex adaptive systems of human habitat that emerge at convergence points in the four environments. In plainer English, cities are the thing we build when people decide to live in proximity to each other.

It’s important to understand how potent that proximity is. The space/time paradox of cities is that people trade space for serendipity. Living in close proximity to other people reduces the time cost of interacting with them, which in turn makes interactions happen that otherwise wouldn’t. Throughout history more and more people have chosen this tradeoff.

And then, for a brief moment, it appeared there was a way to have it all. If everyone had a car, we could deconstruct the city, atomizing it into isolated buildings connected by infrastructure that would let us quickly cover those distances. Then we’d gain lots of affordable personal space, while keeping the serendipity city life. And for a few years, when that first wave of suburbia had not yet been crushed by the traffic of everything that came later, it worked.

Unfortunately, Suburbia doesn’t scale. Cars require a lot of space, and for a car-only system to perform well, things have to stay spread out. Once an area grows past about 5k people per square mile, traffic congestion starts to degrade quality of life, and by 10k people per square mile it’s not consistently reliable. But walking and transit doesn’t start to become convenient until we reach about 10k people per square mile. This is the missing middle of transportation, a gap in the quality of life that’s quite hard for cities to cross.

And so, across North America, we capped development. Single-family zoning, minimum lot sizes, parking requirements, height restrictions, and miles of red tape were used to stop our cities from naturally evolving, in the hope that this would protect their quality of life.

This failed. Low density sprawl creates more traffic than we can ever handle, and the second order effects of capping growth have been tragic: severe housing shortage in our strongest economies4, widespread municipal insolvency among the rest5, and broader harms in every aspect of our society6.

(3) Momentum for reform is building

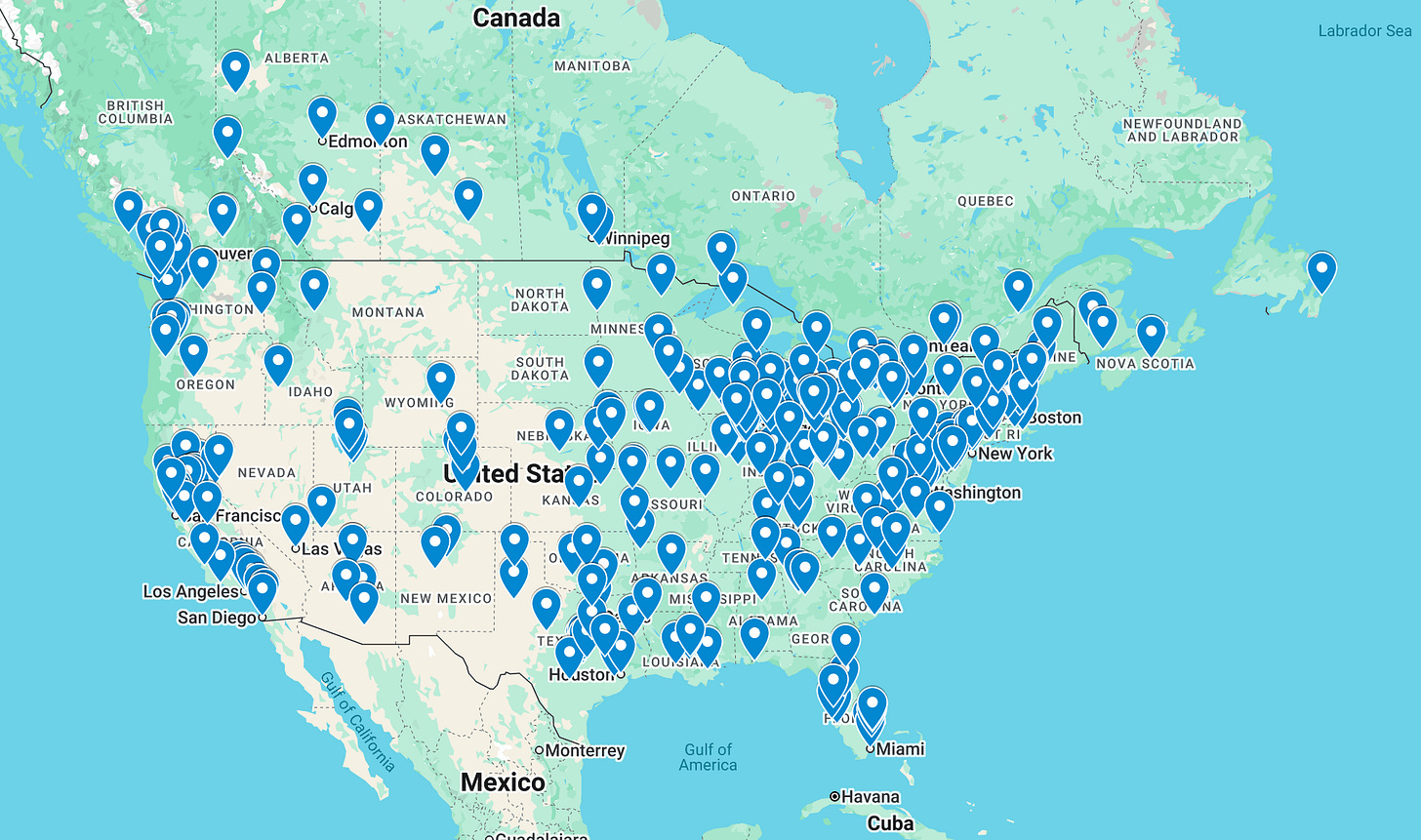

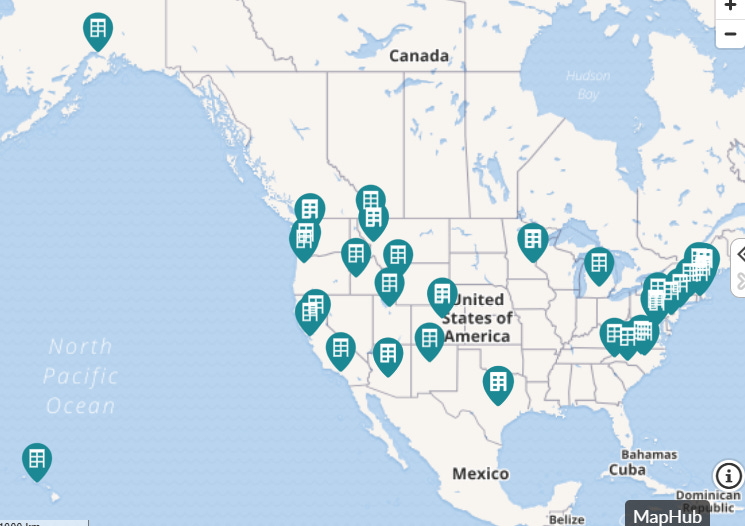

In response to these widespread problems, social pressure is building across the US. People are looking for answers, and the three major movement-building organizations in this space are rapidly growing: Strong Towns, Welcoming Neighbors Network, and YIMBY Action7:

These movements are already winning reform victories nationally. Cities and states are repealing parking minimums, reforming single family zoning, allowing ADUs by right, permitting single-stair apartments, and more. The near future of land use looks very different already.

And there’s no sign of slowing momentum, as new calls to action and new movements continue to emerge. Consider the recent publication of “Abundance,” and the tremendous reform discourse it sparked8, or the efforts of the Roots of Progress Institute to inspire a more positive vision of the future9.

Our cities and towns are searching for a new way forward for our built environment. And, excitingly, now is a great time to be looking.

(4) Transportation technology being deployed today changes the equation

Cities have always formed around transportation technologies, from early fords and bridges, to caravan routes, colonial ports, railways and highways. When transportation changes, cities change in response. And transportation is changing a lot right now.

In particular, there are three relatively new technologies busy climbing their “S-Curve,” that are already affecting cities, or have high potential to impact cities in the future. In order of maturity, these are:

Remote Work. People who work from home don’t contribute to commuter traffic. They don’t need a parking space downtown. Yet they contribute to the local economy by exporting their labor. During COVID we saw remote work send shockwaves through rural America as city workers decamped for the countryside. While remote is not likely to surpass its pandemic peak any time soon, it’s now here to stay, and has particularly changed the economics of rural and exurban places.

Micromobility. E-bikes, scooters, and other light electric vehicles take the range and speed of a bicycle and extend it to everyone, regardless of fitness level. This means more people can move around on the same streets with less need for parking, and potentially changes the “last mile” problem for transit sheds.

Autonomy. Self-driving cars are real and operating across the country today. It’s impossible to predict how this will play out as it scales, but it has the potential to greatly lessen the need for on-site parking even as it could result in longer commutes and more traffic congestion. But even more interesting are drones, that can make increasing volumes of delivery without trucks, reducing pressure on the roads.

Each of these technologies help bridge that missing middle of transportation, enabling cities to incrementally grow past the density chasm without degrading quality of life. For the first time, today’s car-only places have a realistic path to organically mature beyond the scale that cars alone can serve.

(5) Principles for cities

So how should cities operate if they want to harness these opportunities and build a better future? I propose these forward-looking principles:

1 - Plan Roads

Cities almost do this right today, planning highways and “arterial” routes for cars throughout the region, but there are two critical mistakes we must fix.

First, we should never build another Stroad10. That means we must stop allowing driveways on our highways — protect them as true roads, with few intersections and no driveways, and orient commercial development to streets instead. They’ll work better and cost less that way.

Second, we have to plan for more than just cars. Streets must be safe (see the next point) to enable walking, biking, and micromobility. But cities that take this further and have well-connected bicycle networks will be ideally positioned for mode shift to micromobility.

(Note: “Roads” here comes from our definition of Streets vs Roads, road meaning “a path for moving vehicles quickly from A to B.” That means that a “road” includes things like train lines or dedicated bicycle routes, not just highways for cars. But because one of the points here is to plan for many different types of vehicles, and “roads” are colloquially understood to mean “for cars,” I’m wondering if something like “Plan Routes” would be a better mnemonic? Let me know what you think in the comments.)

2 - Design Streets

Streets are the connective tissue that bind our places together. They must be safe, and should be well designed for everyone in the community to enjoy. Fortunately we have a great body of guidance available from NACTO11.

The best guide is called “Designing Streets for Kids.” When children can safely walk and bike through our cities and towns, everything else is easier. Cities and towns will be able to cross that missing middle of transportation, gently maturing over time, making space for future generations, and becoming financially healthier as a result.

The experience of a place is mostly determined by its interfaces — the way buildings attach to the street. If we want to create thriving cities and towns that can incrementally mature over time, we need buildings that face the street with entrances and active use, not driveways and garage doors.

To achieve this, cities should shift their attention away from mandatory car-orientation, and toward human-oriented design. That means things like dropping unnecessary parking requirements and mandatory setbacks, and using elements of form-based code to produce buildings that humanely connect to the street.

4 - Embrace Change

The most important step to unlock transformative housing supply is to allow the next increment of development by right. Instead of an approach that tries to freeze the status quo in amber, cities should reform their development codes to facilitate continuous incremental change.

Cities should consider relaxing or even repealing Euclidean zoning, and instead regulate nuisances like noise and emissions directly. They should develop Adaptive Codes that define what the next level of development intensity looks like for any given parcel, and allowing a property owner to pull a permit to do that project quickly and easily (same day should be the goal).

Finally, putting a bit of nuance on all of this, reformers and advocates have to accept that there will always be people opposed to change. It’s normal to like the status quo and be worried about what will replace it.

We can and should design smart ways for opponents of change to opt-out of the reform in exchange for surrendering their veto over development in the rest of the city. Let these “exclusion zones” be strong but temporary, and require effort to create and maintain them, redirecting the efforts of the vocal minority to control small pockets instead of trying to control the entire city. Consider moving to Land Value Tax to price the externality of exclusion and improve equity.

Conclusion

This was a fun first year! I’m gratified to have recently passed a thousand subscribers, and hope to continue building a community around these ideas. In year one I think I’ve been able to share the big picture, but there’s a lot of nuance and detail left to unpack. We have a whole post-suburban future ahead of us to discover together.

One of my main goals in writing is to invite discussion, answer questions, and explore new ideas, so let me know in the comments: What did you find useful in year one? What are you interested in reading in year two? I look forward to hearing from you!

Here are articles about S-Curves in technology, energy, political science, and project management.

Maps taken from Jeremy’s post, which has a longer analysis worth reading.

https://rootsofprogress.org/

do you have any resources on the ‘misremembered’ suburban timeline? would love to learn more about how they developed before the car-centric model & their previous relationship to cities at large

"Cities and towns that cling to the suburban pattern will struggle and fall behind, but cities that look forward and adapt will emerge healthier and happier." I am not convinced by the first half of your statement; I am inspired by the second half. Why should a suburban area with good access to public transporation and pathways to get into the towns and cities not thrive?