To have a useful and productive discussion about the future of cities, first we need to have a shared understanding of what a city actually is. We all recognize a city when we see it, but because cities make up the environment around us we tend to take them for granted and not think very hard about how they came to be there in the first place. So, this will be the first post in a short series to help us understand how cities fundamentally work—not in modernity or in the US, but across humanity for all time. In future articles I'll refer back to these posts rather than try to re-explain things too much.

The fact that we don't think very hard about how cities actually come to be manifests in a number of widely-held misconceptions, namely that things are the way they were designed to be, or that some thoughtful authority is making conscious decisions about what will happen next.

To pick on one example, in his excellent Substack, Uncharted Territories, Thomas Pueyo asked what makes cities safe.

You’d think by now urbanists would have figured it out, but if that were true, ideal neighborhoods around the world would be popping up and people would flock to live in them… [but] even recent urbanism has failed to consistently create streets that are enjoyable to live on or visit. That means we don’t yet understand the underlying principles of good streets, so we can’t replicate them.

Unfortunately, Pueyo's fundamental premise is wrong. Urbanists have, in fact, largely figured out how to design safe and lovely places. But our cities are not designed by urbanists, because they aren’t designed at all. Our society is a Complex Adaptive System from which cities emerge.

That's a pretty wonky thing to say—what does that mean?

What is a Complex Adaptive System?

A system is, roughly, a group of connected pieces that interact to form a unified whole. An easy example is a computer: the individual parts aren't much use, but when you put them together and power them on, the resulting system is powerful.

When a system is complex, it means the system as a whole does things that we can’t fully model or explain. Weather is a good example—we understand it in general and can make useful forecasts a week out, but the system is too complex to know today where next year's hurricanes will land.

When a complex system is adaptive, it means the pieces of the system act independently and change their behavior in response to changes in the larger system around them.

Complex systems demonstrate something called emergence. My favorite example is the brain: we know that brains are made of interconnected neurons, but we can’t explain how human consciousness emerges from them.

Note that when we talk about systems, complex is not the same as complicated. A car may be incredibly complicated, but we can still model and predict exactly what it will do when the gas pedal is pressed and the steering wheel is turned. Traffic jams are complex: they have certain rhythms that we can observe (rush hour), but can also form spontaneously for no obvious reason, or not form when we confidently expect them. In other words traffic is emergent.

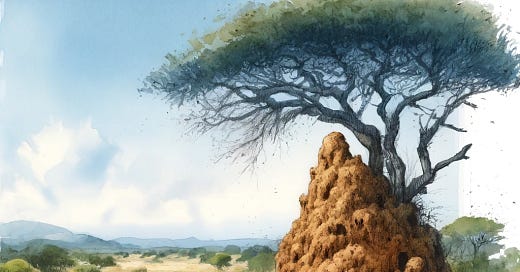

One of the most studied examples of a Complex Adaptive System is the termite mound. The mound is a system, the termites are the agents whose behavior powers the system. No individual termite knows how to build a mound. There’s no termite architect or engineer involved, nor any mayor of the termite city. If you isolate a single termite from the colony, it won’t build itself a tiny termite house. Yet when each individual in the colony responds to the conditions around it, their collective action interacts with physics and the mound emerges.

Emergent Cities

Our civilization is a complex adaptive system made of autonomous agents: humans! We think, plan, and learn. We respond to the conditions around us, working with and sometimes against the system to try and achieve both individual and group goals. And much like termite mounds, the cities we form aren't designed and built by Sim City mayors, they emerge.

Cities emerge from the behavior of individual people and the interactions between them.

Individuals need fundamental things like food and shelter, and seek aspirational things like beauty or status. Throughout human history we've intentionally changed the environment around ourselves in pursuit of these things. We build farms, houses, and workshops. We build walls to keep ourselves safe from external threats. We cluster together to pool resources and cooperate.

Individual pieces of the built environment are planned, designed, and constructed, but the city as a whole emerges from the millions of interactions of its citizens as they respond to their surrounding conditions.

Environmental Cascade and Convergence

Cities don't happen randomly, they appear at convergence points where the environmental conditions are just right to draw many people to the same place. There are four major factors influencing us, four environments we respond to: the Natural, Social, Economic, and Built environments.

Each environment exerts a kind of gravitational pull which attracts us toward (or repels us from) specific places. The environments overlap and interact with each other. They operate at different scales, and in a cascading order over time.

The Natural Environment

The Natural Environment is the most stable and largest scale attractor. It's the first environment, that exists independently of human activity, and usually is the reason why people initially settle in a place. We all need food, water, and a survivable climate. Individual preferences vary widely, but in aggregate people prefer mild climates and sunshine. All other things equal, people seek to settle in places that are safe, fertile, and mild.

While the base level attractiveness of the natural environment tends to be roughly the same over large areas, there are can also be strong local effects in beautiful places (eg. beachfronts) and economically valuable places (rich farmland or minerals, etc).

The Social Environment

The Social Environment is the second attractor, narrower and stronger than the natural environment. Most people feel a gravitational pull to their family, and the social environment defines a range beyond which they won't move: the average American lives within 18 miles of their mother, and only 7% live more than 500 miles from their nearest relative. Adventurous individuals do leave their families and venture across the globe, but when this happens in large numbers we tend to see [migrants follow early pioneers](Individuals do leave their families and venture across the globe) and settle in places where there's an familiar cultural enclave to receive them.

The Economic Environment

The Economic Environment is the third force, generally narrower and stronger than the social environment. Within the social radius people are willing to consider there's a strong incentive to move for economic opportunity. Historically, migrants traveled west in search of farmland to homestead. Today it's common to move from rural areas to cities in search of better jobs in specialist professions, or generally strong labor markets where we'll have more options. More recently this pattern changed as COVID adaptations allowed more people to work remotely, so they could keep their income while moving to places with more affordable housing.

People prefer to live close to work, but they're constrained by their wealth, so they'll move to the best location they can afford. This causes significant sorting effects by income; economic shifts, both upward mobility and displacement, are a major trigger of moves.

The Built Environment

The first three environments push and pull us in a broader sense, from one region or one city to another. But within any region, the built environment causes strong micro-level push and pull effects. Travel time is a critical factor; people generally prefer to live (relatively) near to freeways or train stations that can take them to work. Different people prefer different housing types, or different hobbies. Education and public safety are major considerations. Together these factors cause people to cluster more densely in specific neighborhoods within a city, to prefer a particular home, or to enjoy shopping at one store instead of another.

Convergence points

Settlements emerge where environmental forces attract many people to settle. Since people are an attractive force (social and economic), a virtuous cycle of growth can occur. The more stronger the attraction, the larger the city that emerges.

When many people converge into a city, the land at the convergence point becomes extremely valuable. We can see the aggregation of our collective preferences reflected in land value. Strong Towns and Urban 3 have talked about the importance of value per acre at length, and Urban 3's lovely value per acre visualizations make the center of gravity easy to see.

City Governance

It's impossible for so many people to contend for use of space without conflict. Controlling the very best locations at the most valuable convergence points is extremely lucrative, and taking control by force is always tempting. Settlements begin as small collections of people, but as they grow and conflicts. Some dispute resolution mechanism must emerge for further growth to occur, aka. local government.

As Cities continue to grow, the number of natural disputes continuously increases, so the local government will be given more power in order to manage the inherent conflict of so many people sharing space. (You may have heard the city's job is to protect "health, safety, and welfare"... this includes obvious things like fire protection or sanitation, but the truth is that a City is mainly protecting its citizens from other citizens.)

While the city remains an emergent organism that can't be truly controlled, when the government has sufficient power it can certainly steer development. In the next essay I'll look at how city government influences a city's emergent growth, and how that steering behavior has changed over time.