The Geometry Problem

Suburbia doesn't scale

I mention “the Geometry Problem” in a lot of posts, but haven’t described it at length yet. I think this concept logically follows my previous post, so today’s the day. So what is the Geometry Problem, and why does it matter?

Simply put, the Geometry Problem is that cars are much bigger than humans. They have quite different spatial requirements, both in motion and at rest, than any other mode of transportation. This is neither good nor bad, it’s just a physical constraint.

But these physical differences mean that when we optimize places for cars, they end up not working well (or working at all) for any other mode. They become car-only places.

Like all design decisions, the decision to make car-only places has tradeoffs. The key tradeoff here is that car-only design requires a large amount of space to work well, and that conflicts with and stifles the natural economic growth of cities. Let’s unpack this.

The big tradeoff: space versus time

The best thing about cars is that they can be very time-efficient. Why?

Cars can go very fast. A Model-T could go about 40 mph. A modern car can comfortably cruise at 100 mph. That’s competitive with all other land-based transportation.

Cars go point to point. You don’t have to travel to and from a station to drive, you just go straight to and from your destination. Even if you had an option to fly or take a high-speed train, the travel to and from the airport/station could easily offset the time saved by the faster vehicle.

Cars are autonomous. Auto-mobile says it all. You control the machine, so your trip starts at the exact moment you want it to, no scheduling required.

These are awesome characteristics for a transportation mode, and they’re the reason that the early modern city planners (and culture at large) fell in love with automobiles and went all-in redesigning our world around them.

But there is one big tradeoff: cars are space-inefficient.

Cars take up a lot of space in motion: In order to safely go fast we need wide roads with long, gentle curves.

Cars take up a lot of space at rest: We need 200-400 square feet of space (depending on the layout) for every parking space, and that space needs to be at-grade (or else we have to build a very expensive parking deck).

Cars contend with each other for space: Lots of us would like our car to be using the same road and parking space at the same time, so we need many lanes and lots of parking to maintain time efficiency.

Thus, to optimize for the car, we need to spread everything out. Speaking purely in terms of transportation design, this is fine. But, unfortunately, transportation design isn’t the only thing we care about.

The economy is spatial

Economic activity wants to agglomerate. This is how and why cities exist - they are convergence points of economic value that attract people.

Cities naturally grow as economic activity increases. Space at the convergence points becomes more and more valuable. To keep the economy growing we use the space more and more efficiently to keep it affordable. At first this means we put buildings closer together and cover more of each lot. Then we start to build taller.

In historic small towns you can still see how this used to work. Right at the city center there are a few tall buildings. Then there’s a Main Street with small buildings side by side. Just off the Main Street you have houses on small lots. As you spread out the lots get bigger. That’s the natural economic shape of a city.

Trigger warning: this idea of space being used efficiently is called “density.” Healthy cities gradually spread out around the edges as they also gradually grow denser in the center.

Car-only transportation conflicts with the natural growth of cities

In rural or exurban areas where space is not valuable, trading space efficiency for time efficiency is perfectly logical. In fact, it’s a great idea! Without cars it’s difficult to get economic activity going in an undifferentiated rural area, but with cars we can get agglomeration benefits over a much larger area, so car travel makes it much easier for rural areas to grow compared to the pre-car world.

Economic growth makes space more valuable, and as space becomes more valuable it’s no longer cost effective to allocate all of it to cars. At a certain point the growth of the city makes the car system degrade. We start having traffic jams. Parking lots get crowded. Growth starts to make quality of life worse, so people naturally become skeptical of growth, and then start to oppose it entirely.

The fact that cities want to gradually densify over time becomes a big problem for a car-only transportation system.

When does this tradeoff happen?

To my knowledge this phenomenon has not been studied in a rigorous scientific way, so instead of data I have to offer a hypothesis. But I’ve moved a lot in my life, and lived in widely different kinds of places, so I have a good hunch. Here’s a plot of the places that I’ve lived for at least two years1, and what I experienced as the ease of driving in each one.

Roughly:

Below 5k people per square mile, driving is great.

Between 5-10k people per square mile, it depends.2

From 10-20k people per square mile driving gets iffy.

Above 20k people per square mile, driving is not always possible.

So growth is good until a certain density, and then growth becomes more and more painful as the transportation system that got us to this point degrades in quality. To make matters worse, transportation planners generally agree that transit doesn’t work well until we get above 10k people per square mile. So there’s this gap we can’t cross, the Missing Middle of Transportation.

Why does this matter now?

We started by noticing why cars can be awesome. America saw that potential, and after WW2 went “car-only” as our transportation model, trading off spacial efficiency for time efficiency.

At the time this made a lot of sense. Every city had a vast area of uneconomic land around it, but this new technology greatly expanded the Marchetti constant, opening all this land for growth.

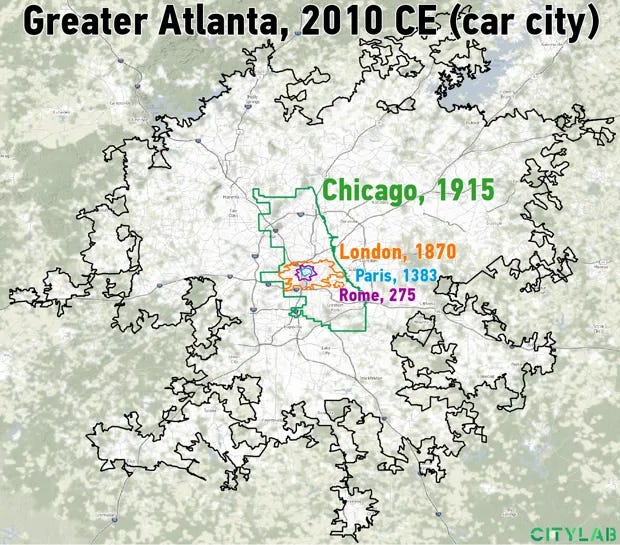

David Montgomery produced this map, which is the best illustration of this phenomenon I could find. Before the Great Depression all our cities had to fit in a much smaller area (roughly that green outline), but after the war they could expand much, much further (to the black outline).

With that much room, the space vs time tradeoff made sense to most people.

The new suburban areas we built started out near zero people per square mile and grew from there. For a while everything was great, and then growth started making quality of life worse (ie we got traffic and parking problems), such that further growth in the neighborhood was undesirable. But that was okay, because there was still plenty of convenient, undeveloped land around to expand into.

It’s obvious in hindsight that this couldn’t go on forever, but at the same time, this pattern of suburban development held up for 50-70 years. We can understand why the mid-century planners weren’t too worried about this.

But, two generations later, most of our metro areas are straining against the Marchetti constant. Regions can partially adapt by building major new economic hubs far off from the original center, but they don’t get the full economic benefit as you can no longer practically commute across the entire region. For example, in a metro area like Houston there’s continuous development stretching 100 miles from Conroe to Galveston, but Conroe and Galveston are realistically not part of the same economy. They don’t get the full agglomeration effect.

So our most important economic centers end up walled-in by a ring of suburbs that stretches as far as people can commute and can’t easily add more people without degrading their quality of life. The result is intense political opposition to densification, which leads to excessive land rent, which manifests as prohibitively expensive housing.

That’s the Geometry Problem.

I think we can solve this; new technology will help, and we’re making some political progress. But it’s going to be hard. The result will have to be a new, Post-Suburban pattern of development; one that allows places to gracefully grow from lower density to higher density over time without degrading quality of life along the way.

You’re welcome to infer from this that I’m at least 22 years old :)

The 5-10k zone is the most challenging. In places that were built before cars, the layout is usually small blocks with sidewalks and on-street parking. These places can grow to around 10k per square mile without much difficulty. In post-war suburban development with circuitous street layouts and little to no on-street parking, growth starts to hurt much earlier.

Great article! I think we urbanists shoot ourselves in the foot when we try to argue that cars are inferior in terms of mobility. It's just not true. But it is true that the costs are not worth the mobility benefits.

One complaint: I read a decent amount of history and Marchetti's Constant is one of the worst theories I have ever read. It's a great construct for understanding the modern world, but it's completely misleading for any time before the nineteenth century. Commuting itself is a relatively new practice. Maybe you can find some odd cases of it as Marchetti did, but it was not a norm in pre-industrial society.

Thank you. Wonderful piece.

I’ve thought a lot about this, though not particularly systematically.

I think many metros would benefit by eliminating cars from accessing the downtown metro (much of Manhattan would be improved by eliminating passenger vehicles and limiting trucks and delivery to specified corridors).

The improvement of battery technology has made personal mobility options much more attractive.

My family lives in Seattle, in a dense by Seattle neighborhood but not downtown. We have a folding electric scooter that cost 400 dollars that makes the bus system here much more usable. We have one car, but that scooter has meant we haven’t needed a second car. Public transit systems could probably be optimized around such solutions, giving people much wider range of what amenities are served by a transit corridor (and might be a way out of that transit trap between 5k and 10k people.

The problem is primarily political. Seattle is on that bubble of density, and a lot of people oppose new development because of parking, but the transit system doesn’t really let you live a car free existence either, and plans to expand the transit system are glacially slow.