I believe we're near the tipping point of a new, post-suburban development pattern emerging due to changes in transportation, land use, and finance. In the next three essays I'll look at each of these elements, how they're changing, and why it matters. We'll start with Transportation.

Americans today live in the world of the automobile. Cars have unlocked vast quantities of land around our pre-war city centers for development, which led to a boom in affordable housing and economic development as cities rapidly suburbanized after the war. Unfortunately, cars have a geometry problem: you can't fit very many of them compared to the number of people who want to live and work in high-demand places. This results in a hard cap on land use intensity in the suburbs, which limits agglomeration effects and creates artificial scarcity.

Simply put, Suburbia doesn't scale.

To unlock a new generation of economic growth, we need to come up with solutions that overcome this geometry problem and allow cities to grow past the limits of car-only transportation. Fortunately, there's been a lot of progress on this front in the last two decades.

I see three major transportation innovations that are already here and have the potential to reshape our cities as they mature and move mainstream. In order of “realness,” they are:

(1) Remote Work

Remote work has been growing quietly in the background since at least the 1970s. It ramped up gradually in the 2000's, especially among tech companies, as internet bandwidth and supporting technologies got better. The pandemic kicked this into overdrive, with almost everyone who could possibly work remotely forced to try and do it. Pre-pandemic about 5% of workers were remote. Post-pandemic about 20% of the US workforce is either fully or hybrid remote -- ie about 28 million of the ~143 million US workers in 2023.

Remote Work is a transportation technology because it eliminates the commute some or all of the time, and for full-remote workers it severs the requirement to live within commuting distance of a workplace. On net this causes three major effects:

Reduced demand for workspace in central office parks (or "downtowns" that reduced themselves to office parks in the suburban era)

Marginally reduced demand for commodity housing on commuting corridors to office parks.

Increased demand for housing in areas with high perceived quality of life.

The last is a big deal, because it means that low-growth areas now have a new lever for economic development: they can directly recruit remote employees instead of needing to attract employers. This results in better incentives for local government; instead of doling out tax breaks to attract companies in hopes of trickle down benefits for locals, they're incentivized to invest in Quality of Life, which benefits current and future residents alike.

Much like the suburban revolution expanded the Marchetti radius of cities and unlocked huge amounts of low-cost land for development, the existence of millions of remote workers opens most of the country for potential new residents, as long as the cost to quality of life ratio is high enough.

(To get a little more theoretical: this shift changes the balance of the four environments, lowering the attractive force of employment centers while marginally increasing the value of all other land.)

We saw a condensed preview of this effect when ~20 million Americans converted to remote work during the pandemic and relocated en masse, causing housing demand shocks across the country that we're still trying to recover from.

(2) Micromobility

Micromobility (ebikes, scooters, etc.) is a booming industry. Light electric vehicles are quickly becoming popular, so much that they're affecting global oil demand. Even as Americans are buying larger vehicles, the rest of the world is moving in the other direction.

We Americans tend to think of ourselves as the pioneers, but we're by far the laggards in electrification. This makes it hard for us to notice how fast this category of technology is improving, and how much better it is today than even five years ago. But the fact that we're not paying much attention doesn't mean this shift can't happen here.

An e-bike reduces the exertion of biking to that of walking, flattening the city and letting people get to work without needing a shower. Scooters take this even further, providing the transportation characteristics of a bike with roughly the physical exertion of driving. These vehicles provide nearly the same travel speed as cars within cities, at a tiny fraction of the cost, and a significant multiple of the fun. Micromobility is also vastly more space efficient than traditional auto-mobility (much easier to park!).

About a quarter of all trips in the US are less than one mile, and about half are less than three miles. At those distances, e-bikes are very quick, and given their tiny cost compared to an automobile, Micromobility could represent a much cheaper option for many city dwellers

Right now, safety is the biggest obstacle to adoption, but again the US is a laggard here. Countries like the Netherlands have figured out how to make roads safe for both cars and bicycles, and in those countries walking and biking accounts for nearly half of all trips. US cities are starting to bring these well-tested improvements to our streets; as we catch up to Dutch safety standards, Micromobility is likely to change travel in North America.

Cities that embrace this shift will not only benefit from improved public safety, but higher-quality, higher-value growth. Real estate development is largely a parking-optimization game, and any reduction in parking necessary to sell and lease space means developers can bring more income-generating square footage to market. Our older, pre-war cities have the most to gain, as they generally have connected street networks that will be easy to adapt and lots of valuable land currently tied up in low-value parking lots. But there's lots to gain in the suburbs as well, especially increased freedom for residents who can't (or shouldn't) drive (like kids and seniors) but can walk or ride a light electric vehicle if the environment is safe.

(3) Autonomy

Self-driving cars exist. I've watched them drive around San Francisco, and seen video of them operating in Phoenix. This is at least a hundred year old fantasy1, something we would have considered magic a generation ago, and yet most people have hardly noticed. We certainly haven't absorbed the impact of this change.

There's a classic vision of autonomy where our cars are able to take us on long drives while we nap or watch TV, which perhaps makes super-commuting or cross-country road trips easier. A slightly more compelling version of this is the dream that robo-taxis can solve our parking problems by dropping us off at popular destinations and then driving away, but Uber and Lyft have already shown us the geometry problem still applies, and we can expect much of the benefit of "not having to park" to be offset by worse traffic congestion. The most compelling scenario is giving more freedom to suburban non-drivers, especially seniors. I think these early imaginings are fairly obvious, so it's safe to predict that individuals and businesses will try to make them happen.

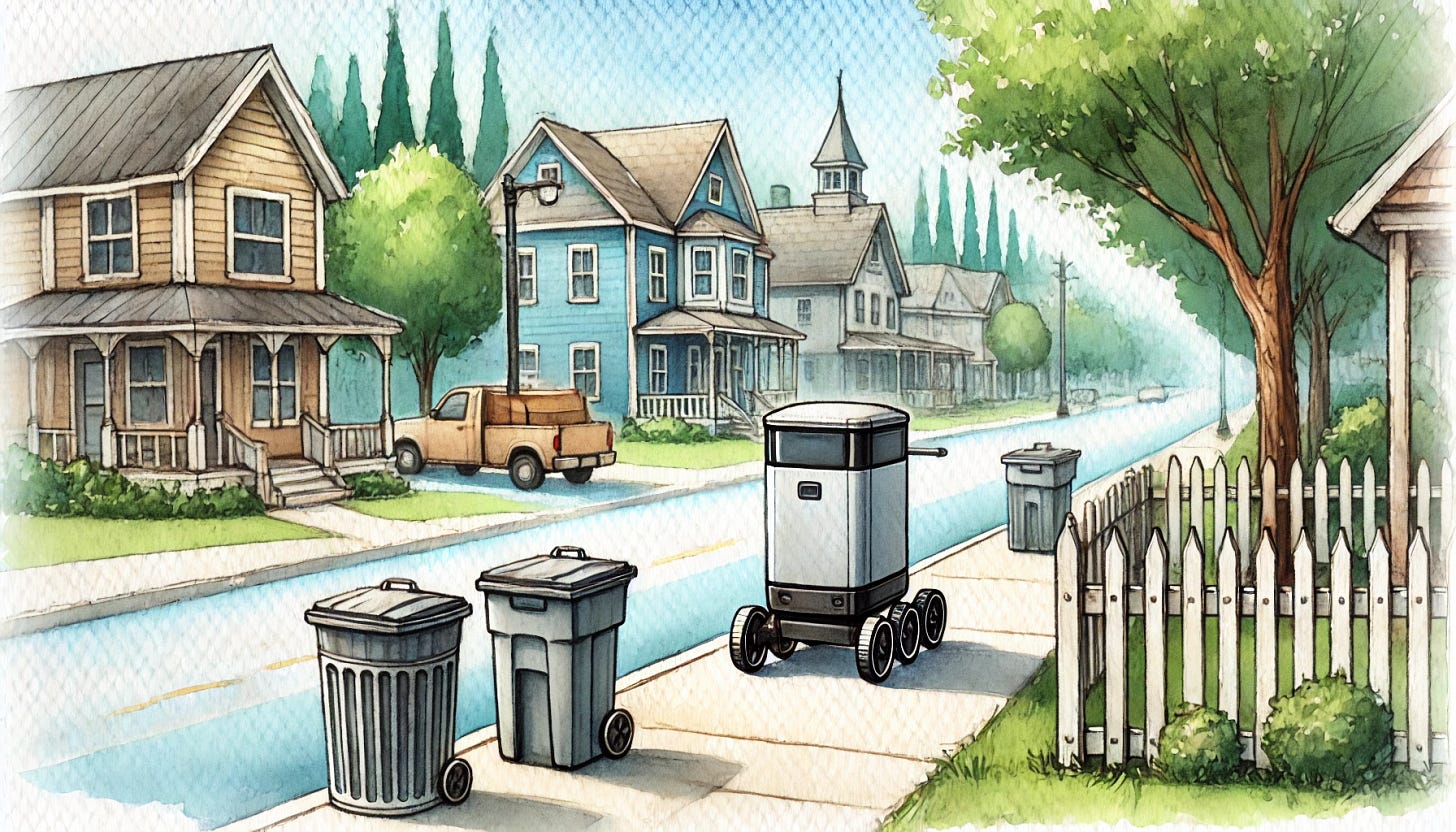

But I think there's a much more profound shift just over the horizon once we decouple the concept of autonomous mobility from the form factor of traditional automobiles. Delivery drones make autonomy much more valuable. Small robots can deliver packages to places that cars can't go, and do so much more space efficiently. These also *already exist*, and are busy schlepping take-out to hungry college students. When these drones are aerial, "that's basically teleportation.”

It's hard to imagine (and impossible to predict) the second order effects.

Trucks are less than 10% of traffic but cause between 35-40% of road maintenance cost. Induced demand suggests that cheaper deliveries will mean more deliveries, so instead of imagining this shift could reduce the maintenance burden on our roads it's more realistic to imagine we could get ever better and faster deliveries from same infrastructure.

Do we need convenience stores when same-day delivery is nearly free, or do we order almost everything online and have it dropped on our porch? Like many other internet-driven phenomena, I suspect there's a Superstar effect, where true megastores like Ikea and charming main street shops do well—visiting these stores is an experience!—but the commodity “big box” stores that dominated the 90s and 00's will struggle and have to adapt (this is already happening).

Conclusion

I have to emphasize, again, that these technologies aren't potential inventions on the horizon, they're all real and working in the wild right now, even though most people haven't noticed yet. We certainly haven't capitalized on these changes yet.

It's useful to remember that cars were invented about 20 years before they became mainstream, and about 50 years before we had reoriented our world around them. I suspect today's major technology shifts will follow a similar progression. If so, then environmental adaptation will start happening in the next few years, and in a generation we'll have shifted to a new paradigm.

Early references that I know of: the John Carter of Mars books imagine "autopiloting flyers," and GM's 1939 Futurama presentation featured “automatic radio control” for cars.