Lately I’ve been having a hard time deciding which things to write about next. I have a number of ideas I’d like to get on paper, but most of these are big ideas that are built on a number of supporting observations or arguments that are also not widely written about, so in order to write about the thing I really want to write about, I might need to write 3-4 preliminary essays to build up to it. Given I only have time to write an essay or two each month, it takes quite a while to build up to big ideas this way.

Today I decided to try something a little different: I’m going to float a few related ideas without explaining them in depth, and I’d be grateful if you’d leave a comment (or reply) with your thoughts on how this works, what questions you have, and whether you think anything here needs more explanation.

So, today here are several related ideas I believe pro-housing, abundance, and Strong Towns advocates need to understand.

Land is the unbreakable monopoly

Very briefly, I think it’s important to state two banal ideas:

Land is a fixed resource — the most important of the very few fixed resources in the world. An individual property owner has an unbreakable monopoly on the occupancy and use of a specific place on the surface of the earth. This isn’t a bug to be fixed, it’s a feature at the foundation of civilization. But it is a monopoly, and understanding it that way helps us understand the economics.

Humans are only so tall — NBA players notwithstanding, people can only usefully utilize the first 10 feet or so above the ground. Also, we know how to build buildings with more than one floor. This is quite a lot like creating new land. It doesn’t quite break the monopoly, but it comes close.

Of course, in the last century Americans have adopted a view that buildings with more than two floors are a bit naughty and should mostly not be allowed. (Who might benefit from that view?)

Real estate appreciation is not wealth creation

We tend to think of real estate as a singular thing, a property, that has some value. This is false. Real estate is two things: land and “improvements” (ie. the buildings sitting on the land). Check your property tax bill, and the assessor will tell you that these two things have distinct and different value.

When property prices rise it’s often described as “wealth creation,” but that’s a deeply deceptive oversimplification. We certainly can add value by improving a property (ie. develop or redevelop it in some way), but most property owners don't do that. It’s usually just the land becoming more valuable.

As a concrete example: if you buy a house and live in it for a while, doing nothing more than basic maintenance, you haven’t added value, you’ve just struggled to fight off entropy. So if you later sell that house for more than the inflation-adjusted dollars you paid for it, that increase in price didn’t come from added improvements to the structure, it came from an increase in the value of the land underneath.

Land values go up when people converge on a place. But rising land values do not make buildings fundamentally more expensive, so if we allowed redevelopment we’d gradually see large lots split into smaller lots, and small buildings gradually replaced with larger buildings, such that the price of a housing unit was stable even as the amount of land attached to the average unit gradually decreased.

Since we mostly don’t allow that, we instead see the cost of housing units rise dramatically where land is in high demand. There’s no wealth creation happening in that case, only wealth transfer. The monopolists are extracting monopoly prices.

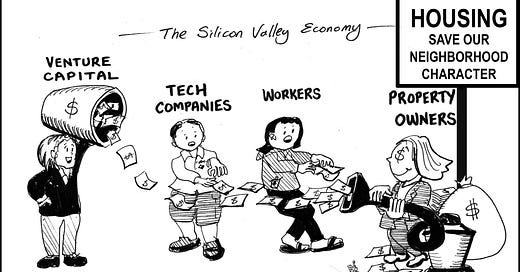

When I lived in San Francisco I saw this political cartoon that captured the dynamic perfectly:

Yesterday’s buyers are standing there with the Great Hoover, sucking all the money they can out of the economy and voting to make sure nobody turns off the faucet.

Rent and sales are transfers

A short corollary to the above: just as land appreciation is not wealth creation, neither is rent appreciation. Value has not been created, money is just being transferred from one person to another.

This is something that really struck home for me when reading “Rents should not influence monetary policy,” by Kevin Erdman. As I’ve had time to digest it, I think this piece belongs in the canon of critical ideas.

Debt is your future earnings pulled forward in time for a fee

Debt allows you to access money now that you expect to earn in the future, but at a cost. When you borrow, you're essentially spending your future income today. The interest you pay is the fee you pay for the privilege of using your future money today.

Debt is neither good or bad, it’s just a tool. But what’s important is to understand debt is not “money from the bank,” it’s your future income. This is really basic finance 101, but, it seems like most people don’t understand this or think of it this way.

When people talk about housing payments it’s just vaguely “the monthly cost of living here,” which is sort of true, but at the same time a mortgage is not just rent you pay the bank. It’s a specific amount of your money that you are on the hook for. If anything happens and you can’t make those payments anymore, you can’t just move. You have to actually sell the house for more than you owe on it, or you’re in trouble.

The amount you can borrow is inversely proportional to interest rates

I think most people vaguely understand this, but incorrectly. Lower interest rates make payments on a given amount of debt lower. Or, they allow a person to borrow more money for the same monthly payment.

In the 70’s we had high inflation, and to get inflation under control we raised interest dramatically to a peak of 15.8% in 1981. Then, for 40 years, interest rates steadily decreased, finally reaching near zero in the wake of the Great Recession.

This meant that people could borrow more for the same payment every year or two. Thanks to the unbreakable monopoly of land and restrictions on supply of new units, the ransom price of housing is the maximum that local people can possibly afford to pay. So for 40 years the available debt ratcheted steadily up, inflating asset prices in general (and housing most of all).

This dampened the pain of housing price inflation for a generation, but that trend literally can’t continue. Central banks can’t really go below zero, and zero isn’t healthy. Despite recent increases we are still in an era of historically low interest rates, there won’t be room for lower interest to compensate for monopoly transfer fees in the future.

Financing can’t make housing affordable

This year I’ve seen increased interest in new ways to financialize housing, most nefariously the 40-year (or longer) mortgage.

It’s critical that we understand that people paying 40-50 years of their future earnings for a house instead of only 30 years of future earnings means they are paying more for that house.

And critically, in today’s paradigm, financing that allows borrowers to take on more debt can only make housing more expensive.

Today the cost of housing is approximately 1/3 of your income for the next 30 years. In our current paradigm, as soon as a minority of buyers are willing to commit 40 years of earnings, the monopoly prices will increase such that every buyer will have to pay 40 years of earnings. That’s how monopoly pricing works.

Vice President Harris has a very slightly better plan, to provide first time homebuyers $25,000 in down payment assistance. So, help them by paying part of the ransom. But that also does nothing to actually lower the cost of housing, it just means that taxpayer funds are getting added to the transfer fee. Again, given the monopoly market, we should expect most of that $25k to be quickly captured by higher prices, especially in entry-level housing units sold to first-time homebuyers.

We need housing to actually cost less

Real estate is two things: land and improvements. Land in desirable locations will naturally rise in value over time. We can only lower the cost of land by making the location less desirable. That can be done, but it’s a bad idea.1

So to lower the cost of housing we have to two levers:

We could find ways to make construction cheaper. This is a hard physics and labor economics problem - there don’t seem to be easy answers here.2

We could use less land per unit of housing. This is super easy! Our ancient ancestors knew how to do this, a lot of their multi-story buildings are still around and in use. Some of them are tourist attractions!

The only obstacle to option 2 is words we wrote on paper. So, let’s change those words and make this happen.

Thanks for reading! As a reminder, I’d love to hear what you think of this format, what questions you have, and whether you think anything here needs more explanation. And if you got some value out of this post, please share it with others.

For examples of value destruction, see every US city building interstate highways through the middle of neighborhoods in the mid century and what happened to the property values in those neighborhoods. Nobody wants to live right next to the interstate.

While lowering the cost of construction is truly is a hard problem, I do think it warrants more attention from the pro-housing audience than it gets. We will have to make progress here if we want to achieve true abundance.

On caveat about the basic maintenance => appreciation /= wealth creation. It’s not just land appreciating in value. As building becomes more expensive faster than GDP growth, replacement values for the existing structure increase as well. So it’s not just the land appreciating, the physical building in place may appreciate (in competition with the real depreciation of entropy).

Did you know that Houston briefly implemented an LVT?