Suppose you’ve been outside lately and heard people complaining about housing. Everyone agrees it’s gotten too expensive, nobody agrees what to do about it, and people seem to like to argue about it.

One line of argument I’ve heard a few times is that the problem is “the developers,” who only build “luxury” housing. “Why don’t they just build middle-class houses again!” If they weren’t so greedy this wouldn’t be a problem.

But the thing about pent-up demand is, anyone who could figure out how to make money selling cheaper houses right now would make a lot of money. And in my experience, people like making money. That strongly implies that it’s harder than it sounds.1

I’m not a developer, but I’ve worked in urban planning and real estate in the past and I know “just enough to be dangerous.” So I thought it would be interesting to try and break this problem down from the developer’s point of view. My goal is to understand what it would actually take to build and sell a new affordable home in Denver, where I live. And to make sure I’m on the right track I asked a developer to check my homework. Here’s what I found.

Picking a price target

To try and deliver an affordable home I first need a price target — what constitutes “affordable?”

The most widely used definition of affordable housing comes from Department of Housing and Urban Development: they define it as housing that costs 30% of gross income or less. Denver’s Department of Housing Stability published figures for 2025 start from an Area Median Income of $98,100, and then take 30% of that to arrive at $2452/mo as affordable. So in Denver a single person earning the area median income “should” be able to afford a $2,452/mo payment.

How much house will that buy? Assuming a 6.5% interest rate (roughly where we are today), and Denver tax and insurance rates, that should be enough for a $400,000 home.2 This roughly matches another rule of thumb, that the cost of a house should be about 4 years of income ($98k ⨉ 4 = $392k).

Now, by targeting median income we’re really targeting the middle of the market, setting a price that about half of people in Denver could afford. So, on the one hand, this isn’t going to be affordable for everyone, but on the other hand it shouldn’t be too hard to deliver a new home for $400k, right?

Let’s try and find out.

Estimating the cost to develop a unit

To figure out what it would take to develop a new home for $400k, we need to break down the major cost components:

Land Cost: the purchase price for a lot. We can look for vacant lots or teardown.

Site Prep: the cost to clear and level the lot for construction.

Site Improvement: the cost of landscaping and utilities. We’ll assume minimal landscaping, so this is mostly the cost of utilities.

Hard Cost: the construction cost of the building.

Soft Cost: the legal, design, engineering, and permitting fees to do the project

Developer margin: what the developer gets paid for doing this work

Let’s estimate these and add them up and see where we land.

To determine the land price I went looking for vacant lots for sale in Denver. I think this one is a pretty good representation of a “typical” infill lot available for development in the city. So this puts our land price at $56/sqft.

To estimate the other costs and soft costs (Site prep, site improvement, hard cost, soft cost) I did a lot of digging online and sanity checked my numbers with a developer. We came up with these numbers as good enough for napkin math:

Site prep: $3/sqft of land

Site improvement: $5/sqft of land

Hard Cost: $250/sqft of building

Soft Cost: 7% of Hard Cost, or $18/sqft of building

To turn these into actual costs we have to decide how big of a home we want to build. Just as a starting point, let’s aim for a 1,500 sqft house — big enough to be comfortable for a family, but still relatively modest.

Finally we need to pay the developer. To keep this example easy to reason about, we’ll imagine it’s a small project that a developer will do with their own cash.3 This would be a bit unusual, but it doesn’t change the final numbers for the project by too much, so it’s worth the simplification.

How much should the developer (try to) pay himself or herself for a project? Since we’re assuming the developer is paying for this project with their own cash, the first thing to consider is what they could do with that cash instead. Just putting it in index funds would return around 10% most years. So, to think of this another way, if the developer does all work it takes to build a building, and they only earn 10% return on cash, they were working for free. As a rule of thumb, a rational developer shouldn’t pursue a project unless they think they can earn a 20% return. That leaves room for things to go wrong, and for the developer to still get paid for their efforts.

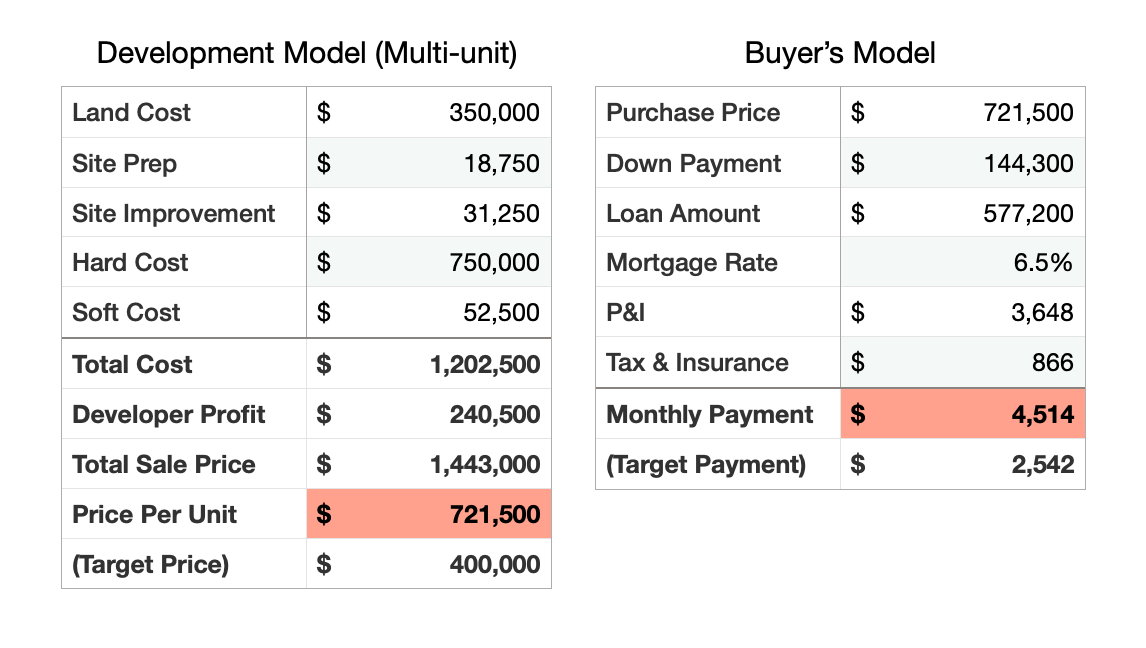

Modeling the project

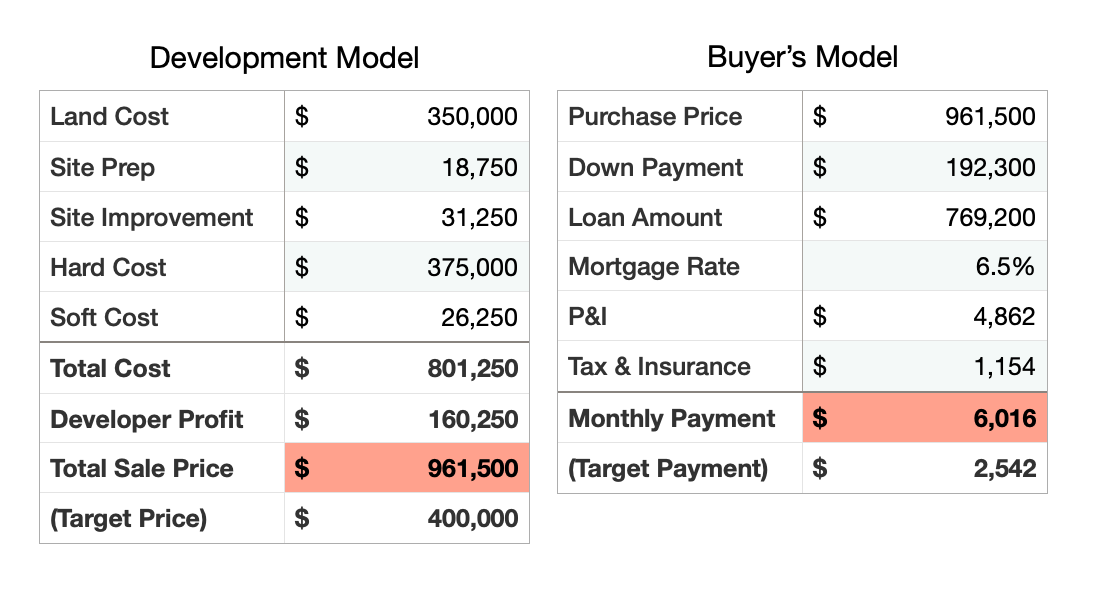

If we plug the numbers we’ve come up with so far we get an initial estimate for the cost of this house. And, unfortunately, the model says this house will cost $984k — more than double our target price.

The first thing that we should notice is that the price of the land ($350k) consumed most of our $400k budget. How cheap would we need the land to be to pull this off? Unfortunately even setting the land cost to zero isn’t enough…

The second problem we have is that construction is really expensive. Even if we magically got the building for free, the land and site prep costs are enough to take us over budget.

Well, is it the greedy developer’s profit that’s the problem? Nope. Free development helps less than free land or free construction.

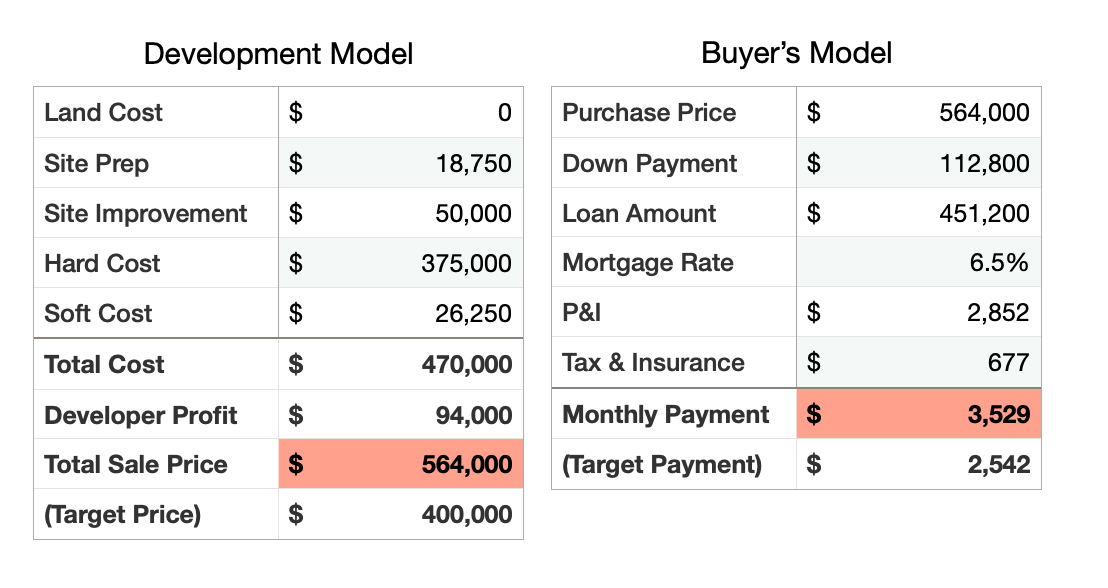

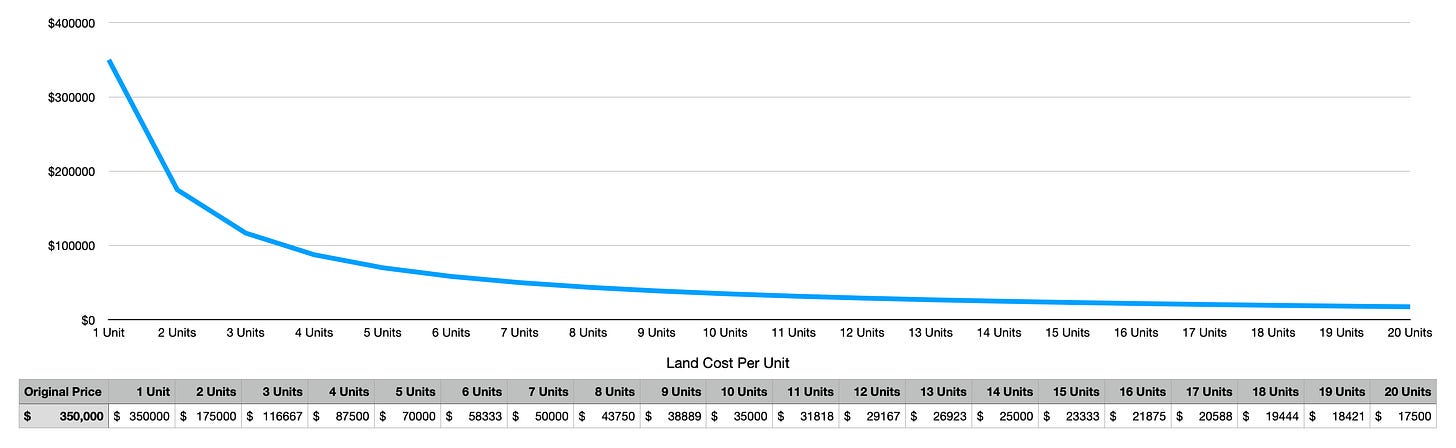

So we’re going to have to find another lever to pull. Since the land cost is the biggest up front cost, let’s take a harder look at that. What if we cut the lot in half and build two small houses instead of one? On the developer’s side the cost goes way up: he’s still paying for the lot and now we’re doubling the construction cost by building two houses. But on the buyer’s side the land area, and the cost of the land, is cut in half.

Ok, this is promising! If we keep splitting the lot into more units, maybe we can get somewhere?

Unfortunately, all we’re doing here is incrementing the denominator… Going from 1 to 1/2 is a much bigger drop than going from 1/2 to 1/3, and so on. Once we’re in the 4-6 unit range, going further isn’t helping very much. Also, we can only fit 3-4 small homes on a lot before we’d need to go to more of an apartment-style building.

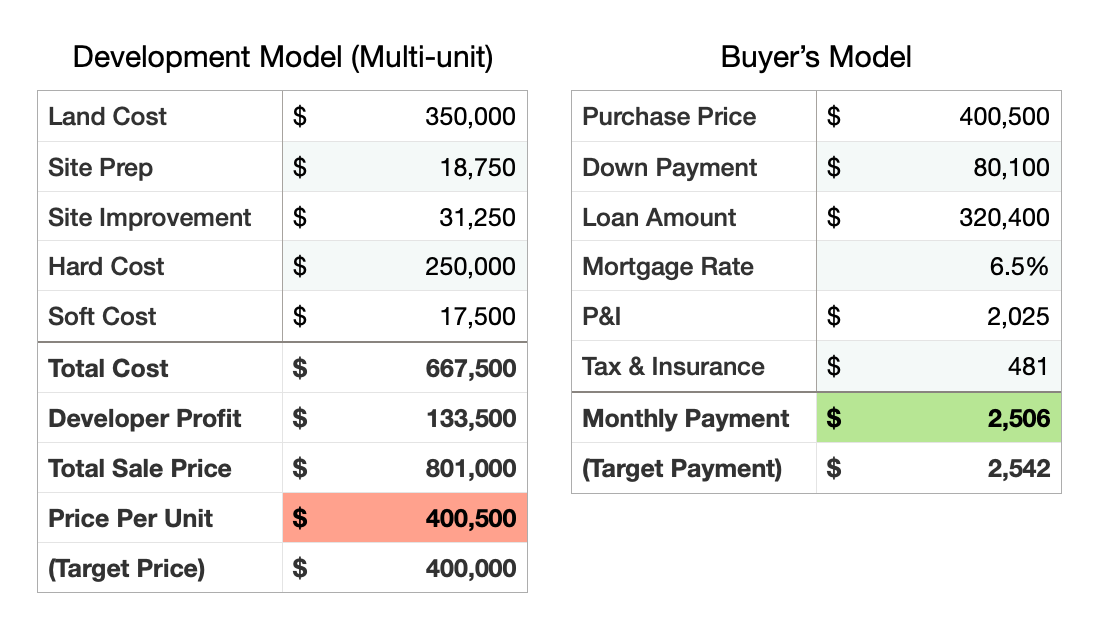

Oh, and we’re not legally allowed to do this. The zoning for the lot in question doesallow two units (go Denver!), but only two. So, let’s go back to thinking about two units.

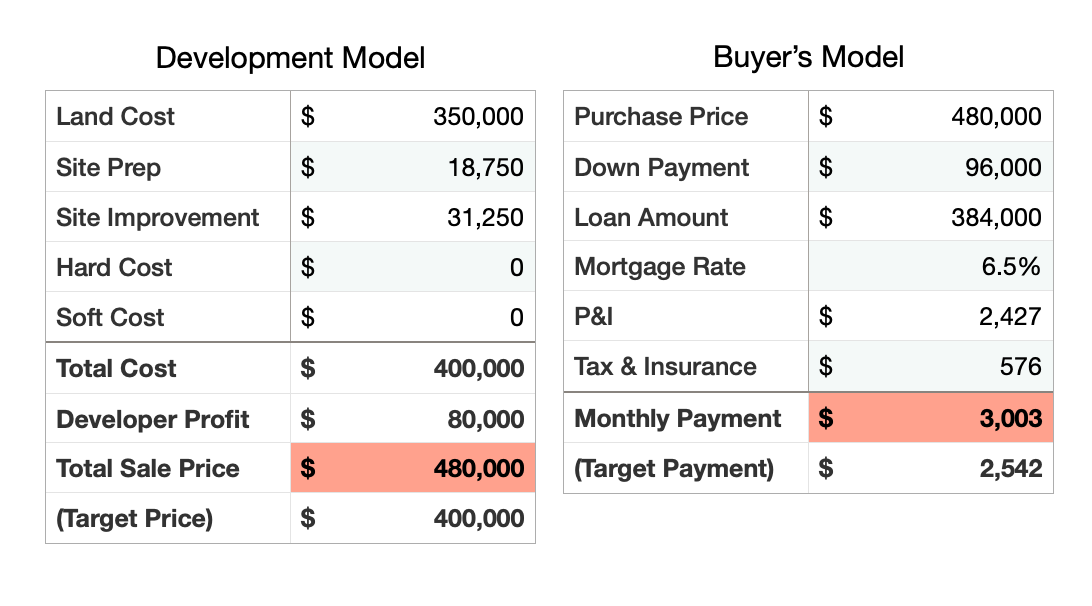

At this point, the only big lever we have left is the size of the units. Now, the cost of a house doesn’t actually scale perfectly per square foot — some costs are fixed, for example the cost of kitchen appliances, or bathroom fixtures, is not determined by the size of the kitchen or bathroom. But, for purposes of napkin math, we can try shrinking the house down until we hit our target budget.

As it turns out, if we shrink down to two tiny homes — 500 sqft each — the numbers just work out.

But, is this really a viable solution? In Denver, you can easily rent an apartment larger than 500 sqft for $2,500/mo. I’m not saying there’s no demand for tiny homes on small lots, but this feels like a risky project that would be hard to sell after building. So, what else could we do?

What about rezoning?

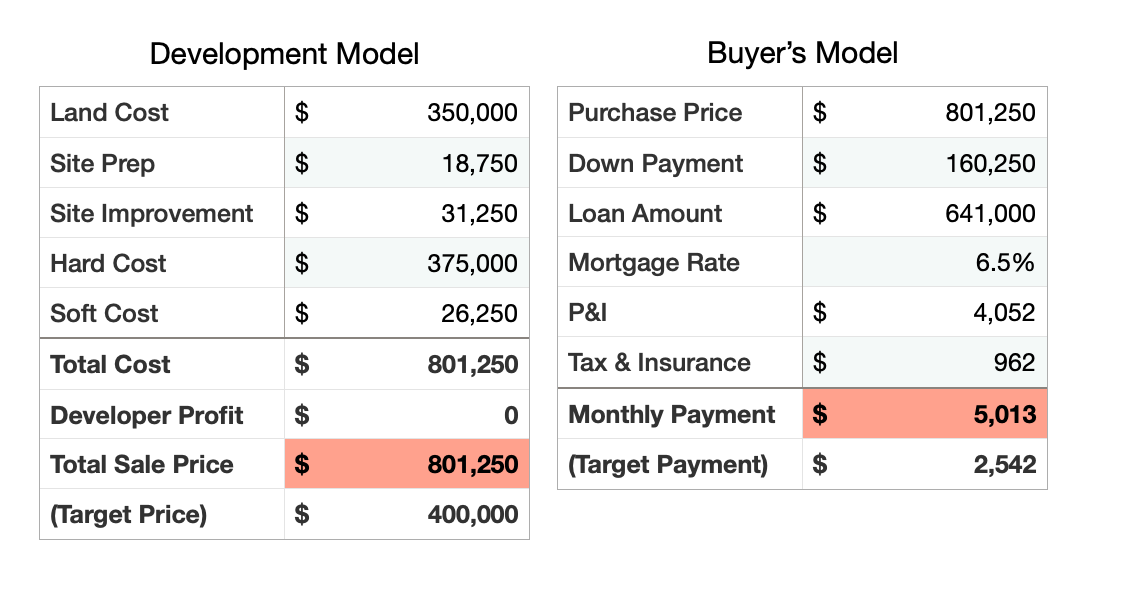

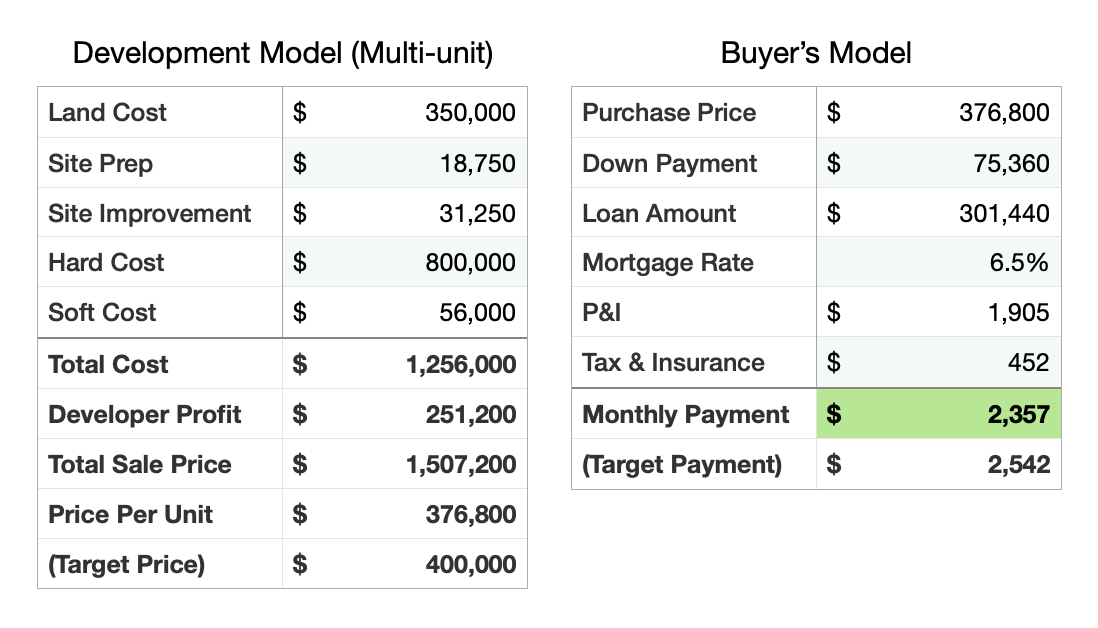

Let’s revisit the land cost one more time: what if we got a rezoning and could go back up to four units?

This is potentially more compelling. Reducing the land cost means we can make the homes bigger, and at 800 sqft per home, we’re closer to the “2 bedroom apartment” than a studio. The building is probably a four-plex that looks like a big house, or perhaps four little cottages. And at $377k, for new construction, we might find some interested buyers. But of course, remember this requires a rezoning, which means the developer probably has to spend several years fighting for permission to do the project.

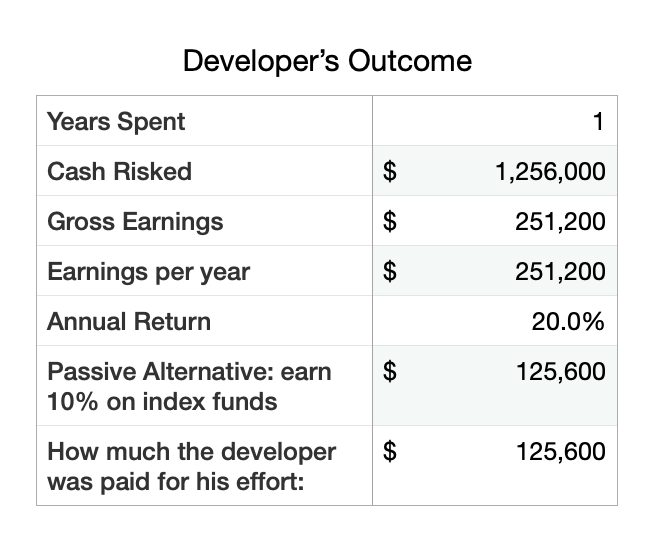

Now this whole model so far has been assuming the project could be permitted, built, and sold in about a year. That’s not a very realistic timeline — most projects take several months to get permits even without variances or rezoning. But let’s take this as a best-case scenario and imagine the developer’s outcome:

Remember, the developer is choosing to do a bunch of work in hopes of earning more money on his cash than they would if they just put it in the stock market and did nothing. In this best-case scenario, the developer earns 20% return on investment, which is 10% better than they could make in the stock market during that time. By doing the project, they’ve effectively paid themselves $125k for one year of work. Seems good!

But if we are more realistic and assume the project takes 18 months to get rezoned and permitted (still might be too fast), and then another 18 months to build and sell, the developer’s return on labor is quite a bit worse. To properly estimate that we’d need to set up a more detailed model that takes into account *when* the developer has to put in different amounts of cash. Explaining that would be outside the scope of this post, but I did look into it, and concluded that in this scenario the developer’s profit after opportunity cost would be around $90k total, meaning they only paid themselves about $30k per year to do the work. For the kind of person who theoretically has $1.2M cash on hand in the first place, doing a lot of hard work to earn an extra $30k a year is probably not very compelling.

On the other hand, if Denver proactively reformed its zoning, a project like this would be a more viable option for providing some relatively affordable new-construction units.

Conclusions

These are the conclusions I drew from the development model — my hesitations and uncertainties about the definition of affordable housing aside.

(1) Filtering is crucial.

There’s broad agreement among researchers and housing advocates that one of the most powerful tools for providing affordable housing is “filtering.” The idea is: when the wealthiest people move into expensive new construction homes, they sell old home to someone slightly less wealthy, who in turn moves up and sells to someone slightly less wealthy, and so on, until the least nice homes in the city open up for lower incomes than previously.

For some, the idea that we’ll improve affordability through filtering is unintuitive and unsatisfying. They don’t want to see new construction at high prices, they want to see new construction that’s cheap. But this exercise shows us, new construction is just never going to be super cheap.

I think a good metaphor here is the car market. We all understand that, while new cars come in a range of prices, they are, in general, pretty expensive. If you want a cheaper car, you buy a used car — we have lots of good used cars available at much lower prices than new cars.

We should think of housing in the same way. Since new construction just isn’t cheap, we’ll get more leverage by adding new houses for people above the median income, so they will move out of their used houses and make those available at more affordable prices for people below median income. This is more practical and more economically feasible, and in fact, a recent study by Boaz Abramson and Tim Landvoigt confirmed that adding high-end housing supply improves overall affordability more than new construction at the lower end.

(2) Incremental Housing is not a half-measure, it’s the bees-knees

Earlier we did the math with the land set to zero and saw how much that helped. That’s what a backyard cottage (ADU) does. The land is already a sunk cost for the primary home, so the added housing unit is just construction cost.

Sometimes housing folks frame ADU’s as a baby step, or “half-loaf.” I disagree! Backyard cottages and accessory apartments will always be one of the very cheapest ways to increase the supply of homes, because they’re the only kind of unit that doesn’t need to incur land cost up front. Also, this kind of incremental housing is probably the most scalable way to add housing supply.

(3) Cities should try to de-professionalize small scale development

Today, getting a building permit in most major metros is laborious, byzantine process that most people find too daunting to try. Some cities today are fixing this by offering pre-approved building plans, so that an interested party can walk in to the city, pick a plan from a catalog, and call a list of registered contractors who are happy to build that unit. More cities should follow suit!

Pre-approved plans take the soft cost and entitlement delay to nearly zero, but it could also knock developer margin off a lot of projects, by opening up the market for normal people to do more projects for themselves instead of as an investment. What if you bought a lot and the city would help you build on it instead of being an intimidating obstacle that only professionals can overcome? Imagine a young professional building a duplex, living in one half and renting the other half. They don’t need to make a 20% margin on that, because the cash flow is going to offset their cost of housing.

That’s how we “unleash the swarm” of local development, produce abundant housing, and drive down cost.

Thank you to Allison Lehman, Deric Tilson, Seth Zeren, and Mike Riggs for feedback on this essay!

In my experience, the word “just” — as in, “we should just” or “why don’t they just” — is a warning sign that the issue is not well-understood.

To estimate this, I took the future value of the series of payments, less (1/12)% per month to account for taxes and insurance, then rounded to the nearest hundred thousand. (Here’s a calculator.) To sanity check this I poked around for listings on Redfin and adjusted the prices to confirm their estimation comes out about the same.

For those who are interested, here’s a bit more on how developers might fund a project.

In the simplest case, a developer really could just use his own cash for an entire project. That makes things quick and easy, and it means the developer keeps all the proceeds from the project, but it also means the developer has to put a large amount of cash at risk in the project.

Realistically, a developer would at least want to finance the construction. While the loan costs take a bite out of the project margins, since the developer is putting in less cash they should earn a higher rate of return on their cash (this is called leverage). In this scenario the developer might be able to spread their cash further and do two projects at a time instead of only having the cash for one.

In most development projects the finance is more complicated. Since developers earn a cut of the overall project, they’ll earn more money for their labor if they can do more and bigger projects. To do bigger projects than they can personally fund, they need to raise equity from other investors and share the profits. Since debt is usually cheaper than equity they’ll look for additional sources of debt as well. This effort of assembling all this money is often called the “capital stack” for a project — being able to go build a capital stack is one of a Developer’s most important skills.

In this case, imagining a small infill project on a single lot, it most likely would be a small/simple capital stack.

When I built my old SFH land cost was 23%. It was a larger then average lot though, if I had gotten one of the more cookie cutter small lots it could have been less. Hard costs (labor and materials) was under 50% (can't remember exactly).

Sales cost (broker commission) and taxes were big. The town for instance charged $50,000 simply for the right to build a unit in the town. There there were all sorts of other town, county, and state taxes and fees. I get the impression this portion of the costs would be scalar, as in if I built a two unit property many of the fees would be twice as much.

Overall, it seemed like the town had calculated what the consumer surplus on new building would be and then charged fees that captured most of that surplus.

"But of course, remember this requires a rezoning, which means the developer probably has to spend several years fighting for permission to do the project."

How much does zoning, permitting, and other local compliance issues add to soft costs? These are examples of soft costs?