The past few weeks I’ve been working on a piece about incremental development. My drafts have gotten a bit long… As it turns out, there’s a lot to unpack here, so I’ve decided to break this into a few pieces. Today I’ll start by defining incremental development, and later will make the case for why the pro-housing community should focus its efforts here.

At Strong Towns, we talk about incremental development a lot, and specifically advocate for the next increment of development to be allowed by right in every neighborhood in America. But what is incremental development, exactly?

Here’s my attempt at a precise definition of Incremental Development:

Incremental development is infill, redevelopment, or horizontal extension of existing neighborhoods, at one level of intensity higher than the surrounding development.

The “next increment” is development “one level of intensity higher than the surrounding development.” To fully explain that we’ll need to unpack it a bit.

Transects

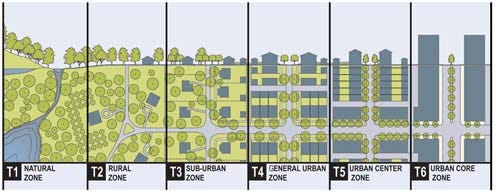

Urbanists describe the change in development intensity over distance usingTransects. We learned this concept from ecology: if you take a slice of an ecosystem, you can often see how the flora and fauna shift as you move toward or away from a key natural feature, like a beach, or the summit of a mountain.

Our human environments show this same pattern, with intense development at the city center that tapers off as you move away.

The most well-known Transect visualization comes from the Smart Code:

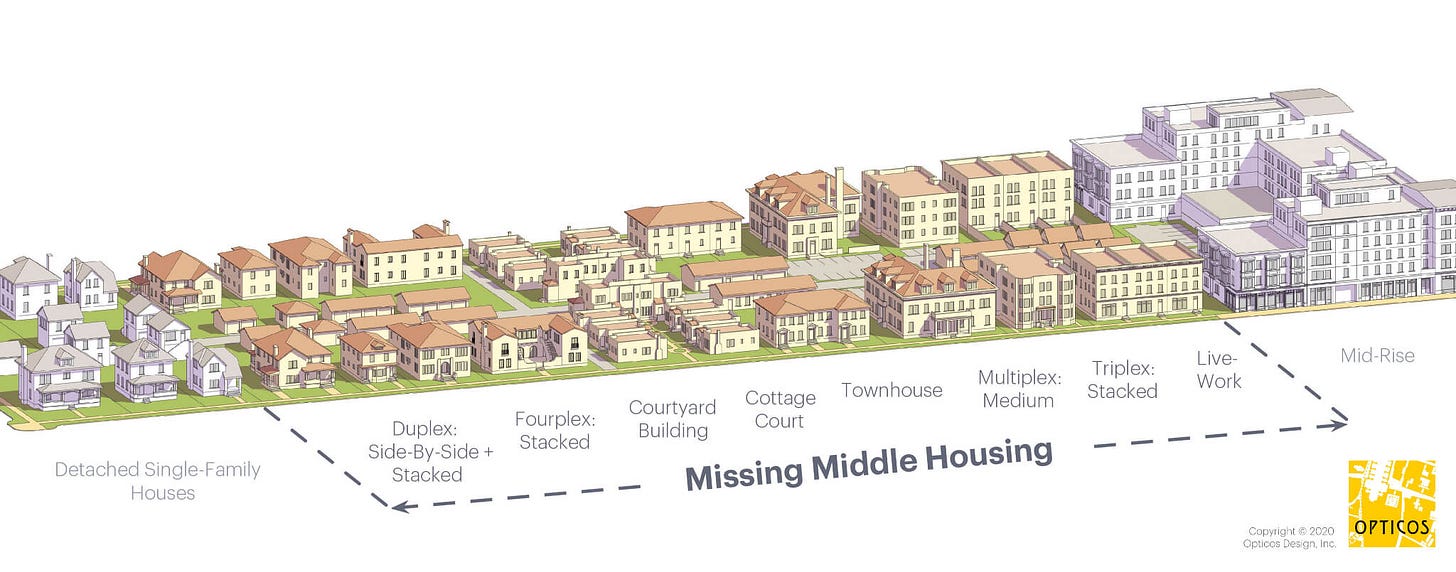

For general discussion, I like the Missing Middle version more.

I’m sharing multiple examples to demonstrate a critical point: there is no “single” transect. A transect is just a line between two points, and a description of how things change as you progress down that line.

We can describe the progression of anything we want using a transect. The next two imagine incremental progression of smaller-scale housing and commercial buildings:

Of course, reality is not as clean as these diagrams depict. How do you categorize a place like this?

We’ve got a strip mall on the left, a residential mid/high-rise in the center, and half of a historic Main Street on the right.

It feels easier looking the other direction. I’d call this a “Main Street” environment.1

When we take an urban transect we’re describing the preponderance of buildings in an area—the area’s most common or prevailing building types. Every place is a mix, but we intuitively perceive a difference in the scale of development from point A to point B shown below, two blocks down the same street.

We might call this “Urban Neighborhood” or something like that, but I think we could agree that it’s one notch “lower” on the development scale than the Main Street shops nearby.

The next level of development

When we label the points along a transect we’re quantizing the change in the form of the neighborhood. We’re taking what’s actually a continuous, noisy change over distance and breaking it into discrete “steps.” These steps are what “one level of intensity” means in our definition of Incremental Development.

A simple example to imagine is our commercial Main Street. One level of intensity could be going from one-story buildings to two-story buildings. When thinking of the “missing middle” transect above, that could mean going from single-family homes to duplexes. At the other extreme, in Manhattan this might mean replacing a 10-story building with a 30-story building.2

Unfortunately, there’s no single, perfect scale we can all refer to that will fit every place. I suspect that we could come up with a few models that would cover most cases, but we don’t have those yet. In the meantime, I do have two rules of thumb to offer:

The steps on the transect can’t be too fine-grained. Saying that a 2-bedroom house is a different typology than a 3-bedroom house and the two can’t fit together in the same neighborhood doesn’t make sense. I wish I didn’t have to say things like that, but one of the fundamental problems we face today is that most of the zoning codes in most of our cities segregate building and land use types far too finely, micromanaging and stifling our cities.

The steps on the transect shouldn’t be too coarse either. Saying that “residential is residential” whether it’s 1 story or 100 stories isn’t economically logical either, and provokes political backlash.

A note on horizontal extension

How do we consider greenfield horizontal development at the edges of our existing cities? It depends on the pattern of development.

To oversimplify a bit, I think that horizontal extension of existing neighborhoods (i.e., what we did everywhere before WW2) is generally good, while sprawling leapfrog development (i.e., most outer-suburban and exurban development today) is generally bad.

Precisely pinning down the difference in these two patterns would take at least another article of the same length, but I suspect that readers of this newsletter are already sympathetic to my oversimplification, so I’ll pile on and say that roughly, “extending the grid” is good incremental development, while building closed-circuit car-only single-use developments detached from a living city is not great.3

Conclusion

Now that we have a solid definition of Incremental Development we can think about it more carefully. In upcoming articles I’ll dig into this more and make the case for incremental development as the preferred approach where the pro-housing community should focus its advocacy. If you have questions or concerns you’d specifically like me to address, let me know in the comments!

And in fact, the City of Denver calls this spot “Urban Main Street 3” on its zoning map. (The “3” means development up to 3 stories is allowed.)

Or more? I’m not an expert on the economics of replacing a tall building with an even taller building.

Planting new towns can also be great, is also yet another entire topic.

One thing I struggle with is how to balance incremental development with places that have had basically zero fro the last decade or more. In my town, we haven't built an apartment complex since 2014, and there is a proposal for in-fill development right in the middle of a giant parking lot in a suburban development. Locals are going nuts saying it's so tall. But it's really only like 2-3 stories taller than other buildings around. Plus we have blocked almost everything for years, so of course this is taller. We really should have had a lot more since then.

I think plenty of towns are willing to consider incremental development. But as soon as you make something by right, $ becomes the major factor, and developers will build as big as they can to make as much as they can. Now you might believe that neighborhoods have no right to preserve what they find valuable. I believe this is what drives many zoning laws. Not because of an unwillingness to bring in new neighbors, but a hesitation to allow developers the right to do whatever they want. There won't be anything incremental at that point. As an example, every new development proposed in our town over the past few years pushes the boundaries and the density well beyond what most would consider incremental steps.