Could we create land use rules that work better for everyone?

Adaptive Code could unlock transformative housing supply without radically changing neighborhoods

In my last two posts I looked at what it would take to build affordable new homes, and how US cities prevent this via regulation.1 I concluded with a recommendation: to improve affordability, cities should strongly consider reducing or eliminating unit count restrictions, and reducing minimum lot sizes.

But there’s a deeper problem in our cities that no one-time change to the rules can fix. Land use regulation is based on a paradigm of stasis: the rules prescribe what can be built on a lot now and forever. Cities can go through all the difficult technical and political work of rewriting the rulebook every generation, but the longer it’s been since the last comprehensive reform, the more that the rules that made sense in the past work against the interests of the present.

To build anything other than the prescriptions of the past, individual projects must go through lengthy and uncertain approval processes. Rezoning takes months or even years, but developers don’t earn money on a project until they sell or lease it at the end, so this time is very costly. And if a developer spends 12 months working on a rezoning and it fails, they’re right back where they started, minus a year of unpaid work. This is too much of a deterrent for most neighborhood-friendly incremental projects to overcome.

Cities should care about managing change; residents who worry about their neighborhoods changing too much, or too quickly, have valid concerns! But, ironically, today’s paradigm of stasis, and its time-consuming discretionary review, pushes developers toward large-scale projects instead. The system gives us periods of little change, punctuated by dramatic change all at once.

But what if we changed the paradigm to intentionally allow housing and development to evolve gradually in response to market demand over time? After all, we don’t need high-rises to close the housing gap. As I previously explored, Denver could solve its housing shortage for twenty years just by adding one backyard cottage per block each year.

I believe we could take a different approach that would expand housing in the places people want to live without radically changing neighborhoods. I call this approach “Adaptive Code.”

An Adaptive Code has two key features:

Instead of what’s allowed being determined by city planners drawing a map, what’s allowed is determined by surrounding conditions.2

Instead of assuming that every place should stay frozen as-is, assume that every place should gradually mature over time.

I explained the core concept in my introductory post a few months ago. Today let’s return to the real-world example of development in Denver that I’ve been exploring in the last two posts, and see how Adaptive Code would improve the outcome.

A simplified Adaptive Code for Denver

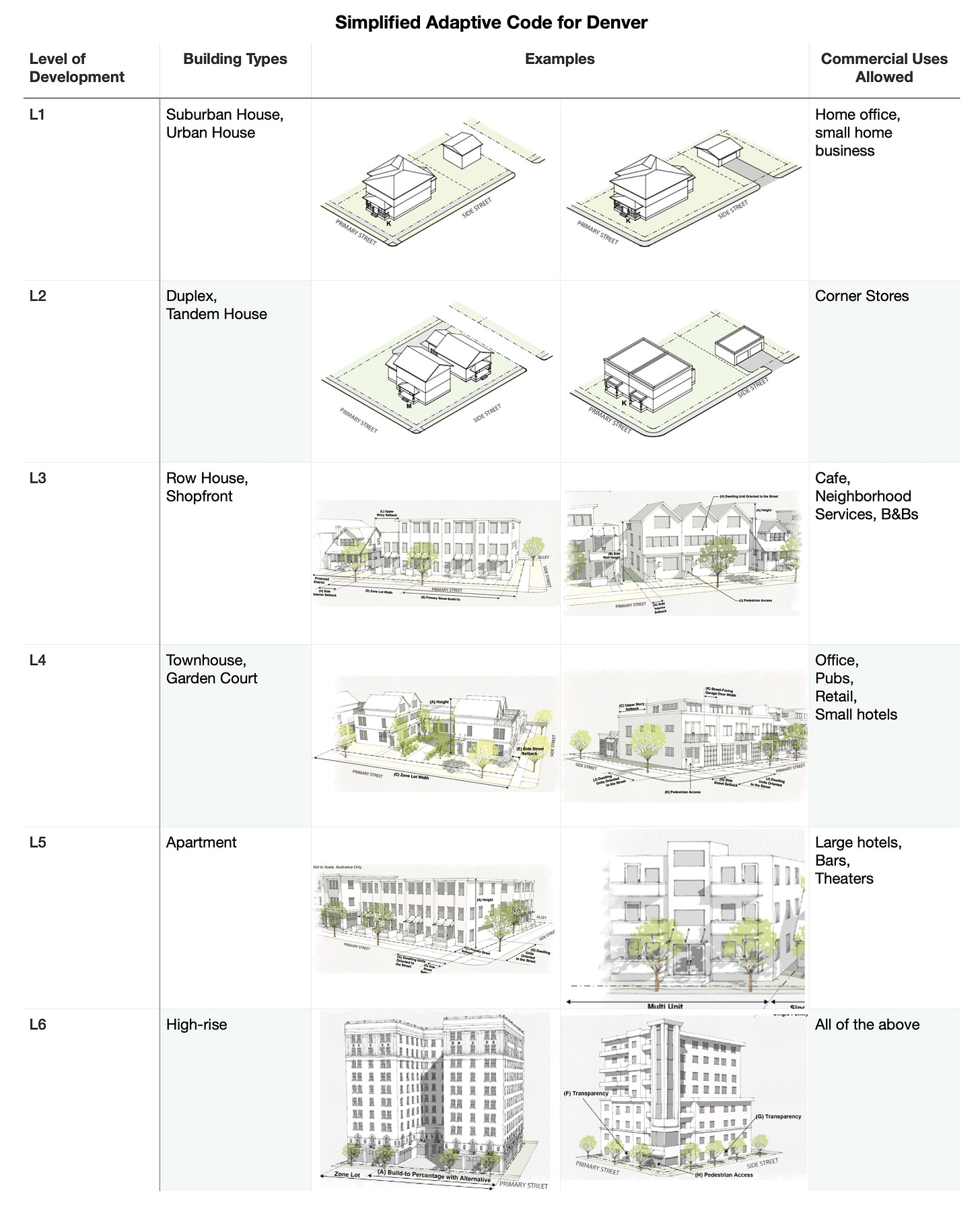

Denver’s zoning code already has great building blocks we can use to imagine an Adaptive Code.3 It specifies a variety of building types that developers can build, with design criteria the buildings need to meet. The code implies a general pattern, where smaller building types are allowed in lower density zones, and larger building types are allowed in higher density zones.

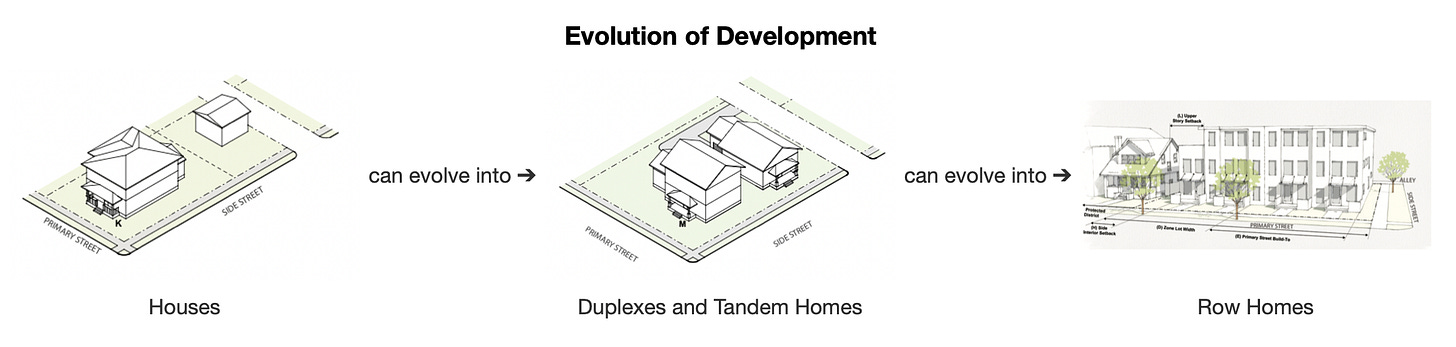

We could take these building types and explicitly organize them into a sequence of increasing levels of development (also known as a Transect).4 For example, we could say that houses are allowed to redevelop into duplexes or tandem homes, which in turn are allowed to redevelop into row homes. Each step in this sequence is one “level” of development.

Instead of distinct commercial zones, we’d allow scale-appropriate mixed-use throughout the city. In other words, commercial activity would gradually increase alongside the level of residential development, so the lowest level of development is limited to home offices, while the next level allows corner stores, and the next allows coffee shops and restaurants, etc.

Put all that together and we end up with something like this as the core of our development code:5

To understand what’s allowed on each property, we’d classify it by its current level of development. Then, on each lot, the property owner would be allowed to build according to the rules for that level of development, just like it works in Denver today. But there would be one big difference: the code would include criteria for succession by right.

“Succession” means a property could be increased from it’s current level of development to the next level up.

“By right” means that no hearing or other discretionary approval would be required.

Adaptive Code is contextual; so the criteria for succession must take the surrounding conditions into consideration. We can use Denver’s existing front setback rule as a precedent:

In Denver’s zoning code (§13.1.5.9) there’s a unique rule for determining the front setback of a property: look at the two buildings on either side of your lot and match whichever one is closer to the street. Some conditions and exceptions apply, so it’s not always that simple, but in most cases this is the rule.

Borrowing that idea, the succession formula could be: if the lots on both sides of a particular property are L1, that property can be increased to L2 (and so on for any given level of development).

A concrete example

To see this approach play out in practice, let’s revisit the scenario we explored in the last two posts. Briefly recapping:

In the first post, I walked through a concrete example using a vacant lot at 3601 Grape Street in Denver. The goal was to build new homes for $400k or less (affordable for Denver’s median income). I concluded that it was possible if we could build four homes on the lot.

In the second post, I looked in more detail the “Two Unit” zoning on the Grape Street lot, and how the it prevents us from building more affordable new homes.

But Denver has a set of rules that would allow more affordable homes to be built: the “Row House” zone. Today we’d have to go through a lengthy rezoning process to build row homes on Grape Street, but what if Denver took the Adaptive Code approach described above?

To start, let’s take a quick look at the surrounding context. If you explore the neighborhood around the Grape Street lot, here’s what you’ll find.

The majority of the neighborhood is a mix of houses and duplexes that look like they were all built around 1950. But there’s a large variety of other building types on the surrounding blocks, including light industrial, commercial, and small apartments.

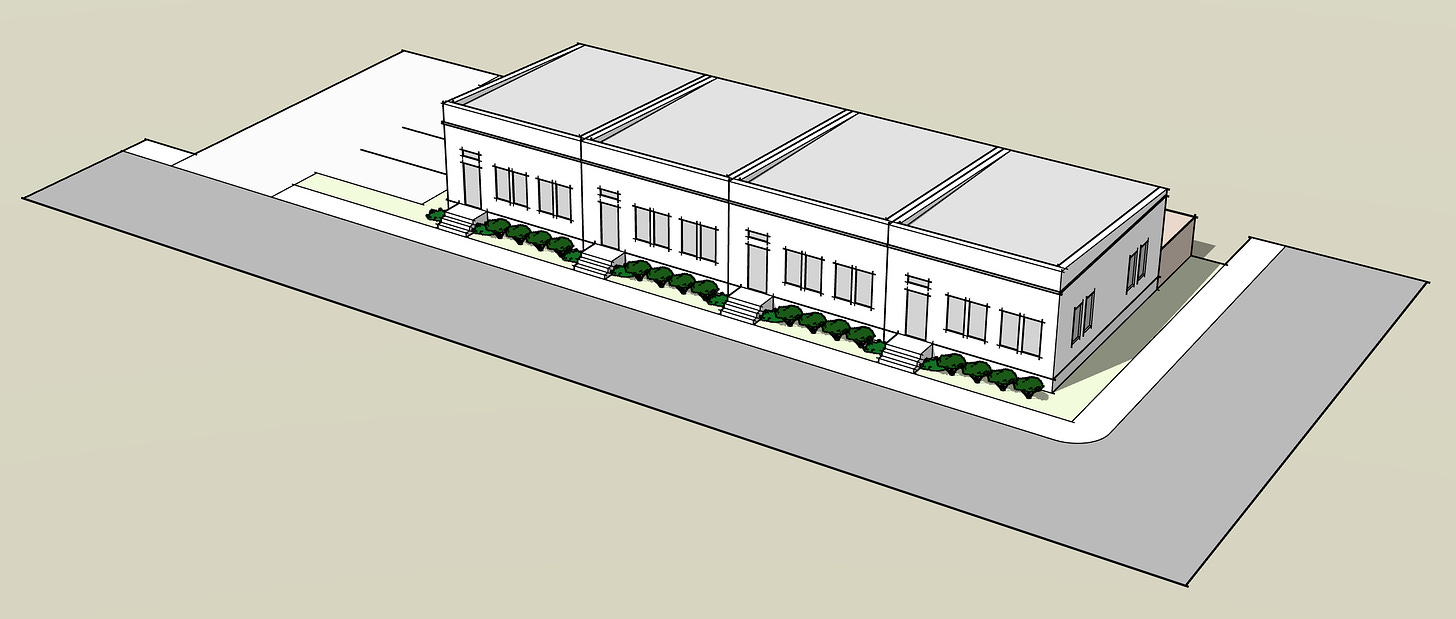

If you look at the frontage on 36th street, it’s obvious that modest row houses would fit in just fine with the diverse mix of buildings that already surround this lot.

In our example Adaptive Code, duplexes are considered “Level 2” development, and row homes are “Level 3” development. Since the Grape Street lot is surrounded by duplexes on all sides, it would be allowed to increase from “Level 2” to “Level 3” by right, meaning we could step up from duplex to Denver’s “Row House” building type.

The result is a set of four, new, affordable row homes.6

As an aside, I hadn’t seen many tiny, one-story row homes like this before I moved to Denver, but the city has a lot of them.

Alternatively, if you prefer (or think the neighborhood would prefer) two story homes with more back yard, we could use a design like this:

There are many other variations that could work, including the four-plex option we considered in the last post, so don’t anchor too much on the design. The key is, under Adaptive Code we’d be allowed to step up to the next increment of development by right. That would make it much easier to bring affordable houses to market without radically changing the neighborhood.

What are we preserving?

The purpose of zooming in on a specific case like this has been to make a lot of the abstract ideas I talk about concrete. The fate of a single random lot in Denver may not matter much, but it demonstrates the paradigm that’s determining the fate of nearly every municipal parcel in the United States.

Today’s regulatory paradigm is to build to a finished state, then prevent change. The assumption is that the presence of a non-homogenous building within any zone is an “encroachment” and “incompatible,” despite the most beloved and vibrant areas of our cities and towns being characterized by a heterogeneous mix of buildings and uses. But this attempt to “preserve” neighborhoods ends up undermining them instead.

We can already see this process unfolding near the Grape Street lot, as homes are starting to be flipped.

Now, there’s nothing wrong with upgrading a home! But we have to understand, these homes are being flipped because there’s significant demand from higher wealth people to move into this general area. Because we haven’t made space for them in the higher-wealth areas, they have to find an alternative. Many of them decide to move into lower-wealth neighborhoods nearby. And because we’re not adding many homes there either, higher-wealth people can only move in by displacing the lower-wealth people who live there now.

If the city continues trying to preserve the buildings in their current form, the most likely outcome is that the existing residents will be gradually displaced as wealthier people move into the mostly fixed supply of homes and upgrade them. We have not preserved “the character of the neighborhood” if all the current residents are displaced.

It’s time for a new paradigm

Cities can and should try to reform the specific rules that limit new housing, including parking mandates and minimum lot sizes. But as long as we continue operating within a paradigm of centrally-planned stasis, we won’t address the root cause of our problems.

To improve housing affordability and reduce displacement, we have to let neighborhoods mature and add new homes where they’re needed. Existing residents don’t want to experience radical change, nor should they. But spending months reviewing each change on a lot by lot basis won’t work; nor will restricting change to just a few sacrificial neighborhoods.

We need a new paradigm that embraces change while being responsive to the challenges it brings. Adaptive Code is my vision for how to achieve it.

Epilogue

Today’s example uses the building blocks of Denver’s existing code to make a hypothetical Adaptive Code for the city. In practice, Adaptive Codes would look different in different places.

Each community would need to make two critical decisions:

What are the appropriate levels of development for our community, where stepping up from one level to the next represents healthy maturation of the neighborhood?

What formula should we use to determine when a lot should be allowed to take that next step?

The critical point is that the community is deciding how it should evolve deterministically, by right; not whether it will evolve on a discretionary, project-by-project basis.

Adaptive Code is novel, and cities that move this direction will have to iterate. The succession formula will encounter edge cases to work out. The steps up in development have to pencil for developers; finding the right levels may take multiple attempts. There will also be special cases, like the land around high-capacity transit stations, where we might want to intentionally take larger steps up. What other considerations can you think of? I’d love to hear your ideas in the comments.

Working this out won’t be trivial, but if we got it right, we’d unlock incremental development, which is the best and fastest path to solving the shelter problem, without depending on subsidies or inflicting radical change and displacement. And maybe, just maybe, we’d end up with land use rules that work better for everyone.

Thank you to Mike Riggs, Étienne Fortier-Dubois, Colleen Smith, and Pam Burleson for their feedback on drafts!

In cities where housing is very expensive, the best lever we have to reduce the cost of a home is to use less land per home. But the most common elements of land use regulation in the US are unit count limits and minimum lot sizes, which specifically prevent using less land per home. Even Houston, which has famously never had “zoning,” has always had minimum lot size requirements.

In this way, Adaptive Code is not Zoning, but rather a Unified Development Ordinance.

I want to emphasize this point: Denver’s code contains many good ideas, and, for the most part, it produces good buildings. I have my critiques: I think the code is more complicated than it has to be, and I don’t like how much of the city it tries to lock into permanent low-density suburban form. But adopting a new code is hard, and I’m certain that many points I would critique were necessary concessions to political reality. I’m glad Denver developed this code, and that we’ve had a chance to see it in action and learn from it for the last 15 years.

I think Denver has a better foundation to build upon than most cities. So don’t take this post as a critique of Denver’s code, so much as an attempt to imagine the next step the code could take.

While the word “transect” does not appear in the Denver zoning code, the code clearly is inspired by the idea of the Transect, and Transect based codes like the Smart Code. In a sense, what Denver did was make a “transect of transects,” where first the city is divided into “contexts” that range from “suburban” to “downtown,” and within each context there is also a series of zoning “districts” that increase from lower intensity to higher intensity.

In this example I’m focused only on residential and commercial development. Denver also has distinct “special context” zones like Industrial, Campus, and Airport, for uses that are generally not compatible with neighborhoods. For today’s example, I’d say that portion of the code works well and should be left as-is.

Per my understanding of the Denver code: to use this exact design, an Administrative Adjustment would be required to allow the development to face the “long side” of the lot rather than the “short side” of the lot, and to set the front setback. But given I’m imagining a significant reworking of the code, I’ll take a bit of license and assume that either (a) we might also tweak the code not to require those administrative adjustments, or (b) that they’d be approved.

I'd love a land use regime that just allows people to build any residential or commercial capacity they want wherever they can get the land to do it, but there will always be fear of "Manhattanization" that makes the easiest fixes much heavier lifts politically.

This has the benefit of being broadly acceptable in every single neighborhood in the city, even out to the suburbs and neighboring cities if you push it at a statewide level. And it gets people used to natural growth where they live, making the case for heavier changes in neighborhoods that truly need them a lot less alien to people's experience.

Plus, as density creeps upward, the case for good walking and neighborhood biking infrastructure increases, bringing back things like Main Street and the local library as parts of daily neighborhood life. This could really start improving a lot of neighborhoods all at once if it could get through.

Really thought provoking! And I appreciate your effort at addressing the difficult challenge of how change is perceived in established neighborhoods.